- Quick Facts

- Saturated Fat: What You Need to Know

- Monounsaturated Fat

- Polyunsaturated Fat

- Foods That Are High in Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids

- How Fat Consumption Has Changed Over Time

- How Saturated and Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Impact Blood Lipid Levels

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Saturated vs. Polyunsaturated Fats: Final Thoughts

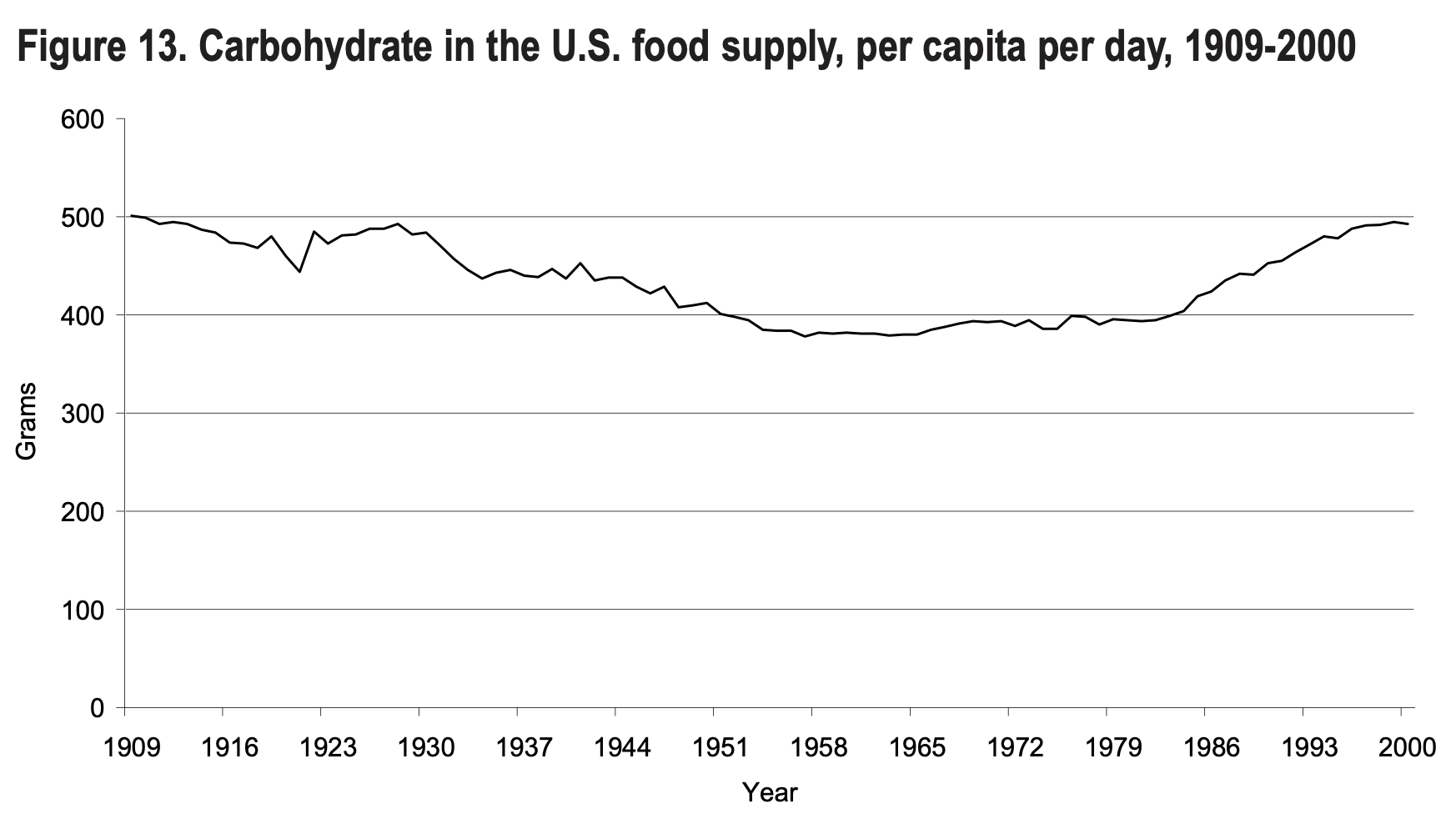

I started embracing a low-carb diet several years ago, in large part because I came to believe that processed carbohydrates — and especially processed sugars — are the primary driver of chronic disease in Western countries.

But recently, I’ve been learning about another type of food that might have an even more detrimental impact on our health. And I’m not talking about saturated fat, as the American Heart Association and other “trusted” sources for dietary information would have you think.

I’m referring to supposedly “heart-healthy” polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), and to linoleic acid (not to be confused with alpha-linolenic acid) in particular.

Quick Facts

Before we take a deep dive into the topic, here are a few key facts to keep in mind as we talk about the health effects of different kinds of dietary fat.

- Polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs) oxidize easily when exposed to heat, air or moisture.

- Oxidized fats cause cell damage, inflammation and metabolic dysfunction.

- Americans consume unprecedented amounts of pro-inflammatory linoleic acid.

- The major sources of linoleic acid are industrial seed (vegetable) oils, corn/soy-fed monogastric livestock (such as chicken and pork), and packaged foods.

- Some experts believe that PUFAs have a worse impact on our health than processed carbs and sugars.

- Saturated fats are not a direct cause of atherosclerosis, because they’re stable and don’t oxidize easily.

- Your genes may play a role in determining your body’s inflammatory response to linoleic acid.

Linoleic acid is the shortest chain of the common omega-6 fatty acids, and chances are that you’re consuming incredibly high amounts of this substance every day without realizing it.

That’s a major health problem because linoleic acid has been shown in several studies to damage fat cells, leading to inflammation and metabolic dysfunction that will ultimately cause obesity, heart disease, cancer, insulin resistance, Alzheimer’s (also known as Type 3 diabetes) or any of the other chronic diseases that affect most Americans.

One interesting aspect of the study I mentioned above is that it demonstrated how the ratio between linoleic acid and palmitic acid (a saturated fatty acid) can determine the rate of cell death (apoptosis). In other words, linoleic acid is less of a problem if there is sufficient palmitic acid present.

But as is so often the case in the nutritional world, you won’t hear about the dangers associated with PUFAs from the sources that are supposed to provide good dietary advice.

For example, as part of my research for this article, I Googled terms like, “Are polyunsaturated fats healthy?”

The answers provided by some of the top U.S. medical outlets were absolutely mind-boggling:

- Cleveland Clinic: Saturated fats and trans fats are bad for you, period.

- Harvard Health: Good fats include monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats.

- American Heart Association: Eat foods containing monounsaturated fats and/or polyunsaturated fats. Polyunsaturated fats can help reduce bad cholesterol levels.

In this article, I’ll dive into the different types of fats and fatty acids and explain their impact on your well-being. I’ll also explain why saturated fats are crucial for your health, why you should stay away from most cooking oils, and how certain PUFAs (especially linoleic acid) are likely the primary driver behind obesity, insulin resistance and many chronic diseases.

Some health experts, such as Dr. Catherine Shanahan, a renewed family physician and author of the book The Fatburn Fix, even argue that the overconsumption of PUFAs has a greater negative impact on our society than processed carbs and sugar.

I’ll also explain the vital difference between how our body metabolizes PUFAs from whole foods versus PUFAs from industrial seed oils and other highly-processed products.

At the end, you’ll find a list of healthy sources of fat and an explanation of why you should largely ignore your total cholesterol and LDL at your next physical exam, instead focusing on fasting insulin, HDL, triglycerides and CRP (as recommended by renowned cardiologist Dr. William Davis and my friend and animal-based diet guru Dr. Paul Saladino).

But before we dig into the issues associated with the consumption of omega-6 PUFAs, let’s talk about saturated fat.

Saturated Fat: What You Need to Know

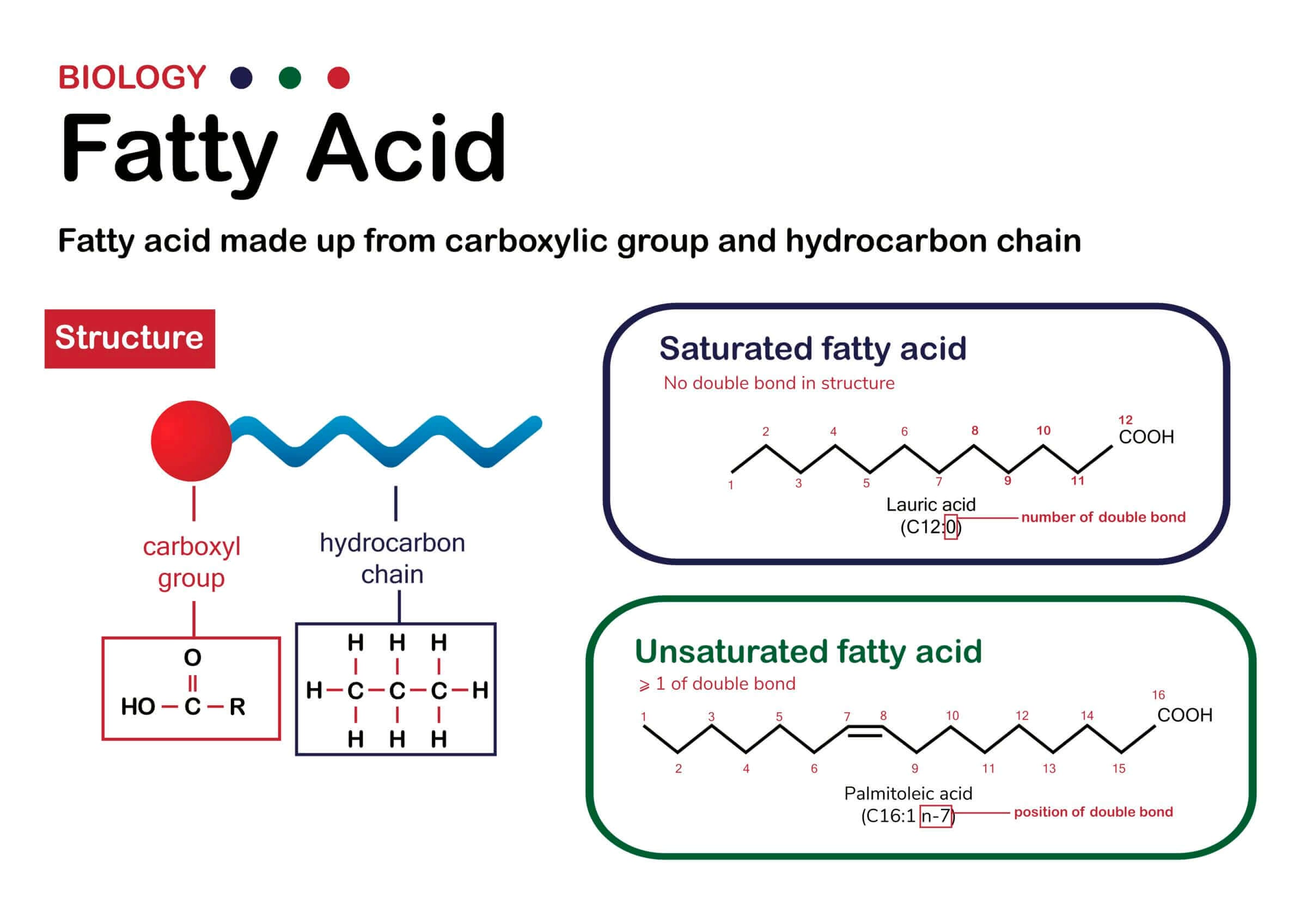

The term “saturated” refers to the molecular structure of fatty acids. Saturated fatty acids have a hydrogen (H) atom on every carbon (C) atom via a single bond. These single bonds are incredibly stable and prevent fat from oxidizing or going rancid.

Saturated fatty acids are why you don’t need to refrigerate butter or tallow (rendered beef fat) (and why these fats stay solid at room temperature).

So if saturated fats are stable and don’t easily oxidize or go rancid, why are they supposed to be bad for your (heart) health?

The Lipid Hypothesis: Correlating Saturated Fat and Heart Disease

German scientist Rudolf Virchow, known as the father of modern pathology, was one of the first to describe lipid (the medical term for fat molecules) accumulation in the walls of arteries at the end of the 19th century.

Coincidentally, cardiovascular disease was a rare occurrence in the United States in 1900. Only ~27,427 deaths were due to the condition, according to the CDC. By the middle of the 20th century, cardiovascular disease had become more widespread, and the so-called lipid hypothesis garnered greater attention.

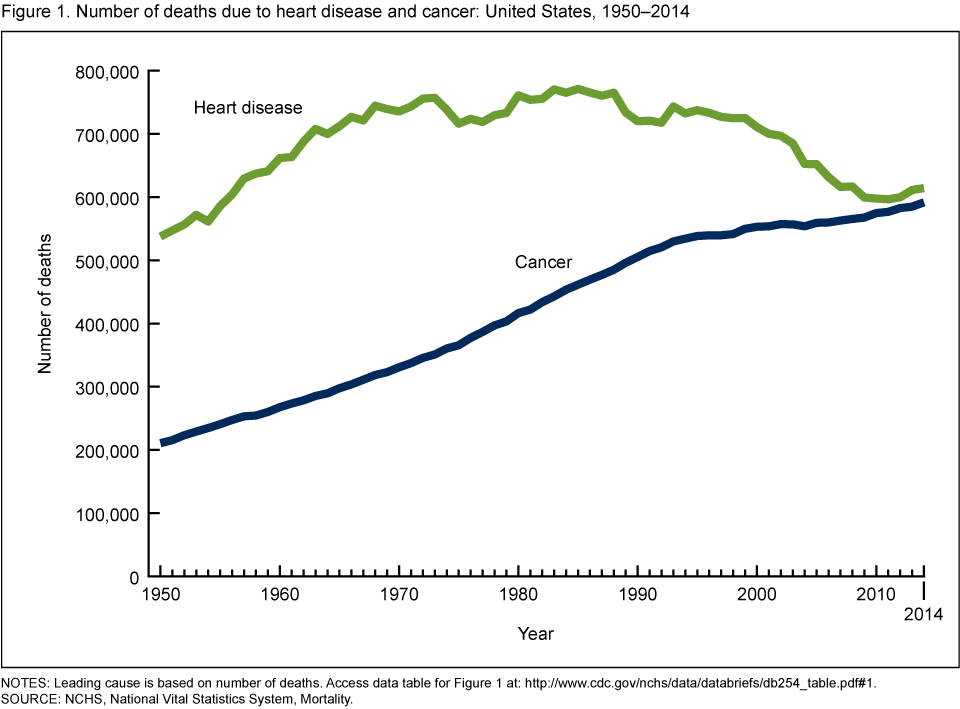

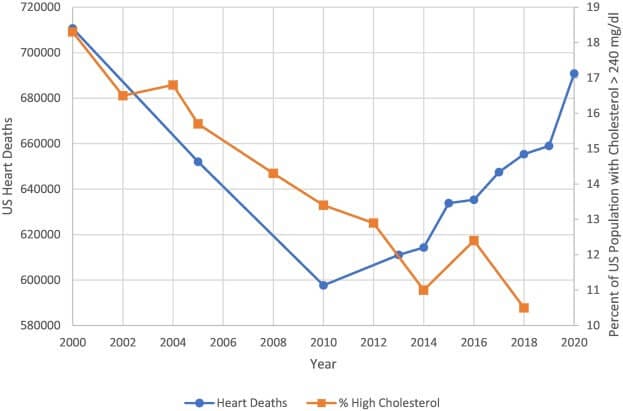

While I admit that diagnosing certain illnesses was more difficult in 1900 than it is today, just looking at the rates of heart disease and cancer in the last 50 years paints a very clear picture (see image above).

The lipid hypothesis suggested a direct connection between the consumption of fat (specifically, saturated fat) and heart disease. And by the end of the 1980s, it was “universally recognized as a law” as one article stated.

That widespread acceptance was most likely driven by Ancel Keys’ Seven Countries Study, which suggested that the countries with the highest consumption of saturated fats had the highest occurrence of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Of course, one of the problems with this study was that Keys conveniently ignored several countries with a low incidence of CVD but a high consumption of saturated fats.

In 1980, the United States published the first version of the infamous Dietary Guidelines for Americans — aka the USDA Food Pyramid, which is now called MyPlate.

The food industry reacted to the public’s new goal of reducing saturated fat intake with the commercial production of trans-unsaturated fatty acids (trans fats, as found in margarine) and other processed fats like hydrogenated and partially-hydrogenated vegetable oils.

Since then, every major health outlet, including the American Heart Association, has claimed things like, “eating foods that contain saturated fats raises the level of cholesterol in your blood. High levels of LDL cholesterol in your blood increase your risk of heart disease and stroke” and recommends to replace foods high in saturated fats with foods high in monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats (AHA).

However, the evidence does not bear that out. For example, the chart below shows a spike in deaths from heart disease despite plummeting cholesterol consumption. Note that according to the study, the decline in deaths prior to 2010 were due to “other life-saving interventions such as smoking cessation, better blood pressure control, reperfusion therapy for acute MI, improved heart failure treatments and the availability of defibrillators” (source).

What’s mind-boggling is that none of the scientists involved in earlier studies attempted to answer the question of how (saturated) fats, which humans consumed for millions of years as part of evolution, would suddenly cause heart disease.

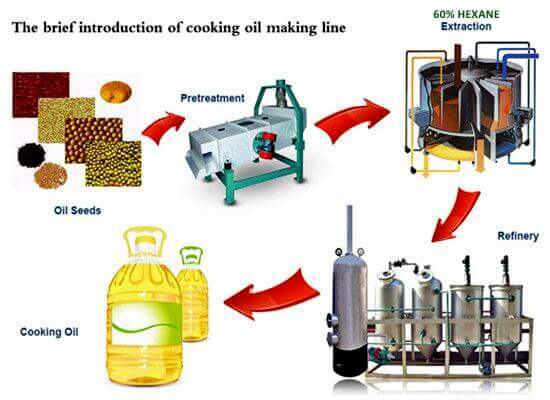

More importantly, why would industrial seed oils that require harsh chemicals (such as hexane) or high heat to get oil extracted from plant seeds be better for our health than unadulterated saturated fats from animal sources?

In what world does that make any sense?

Fortunately, we don’t have to try and make sense of these myths because there are several high-quality studies that confirm what evolution has proven all along: the consumption of saturated fat does not cause heart disease (or any other disease, for that matter).

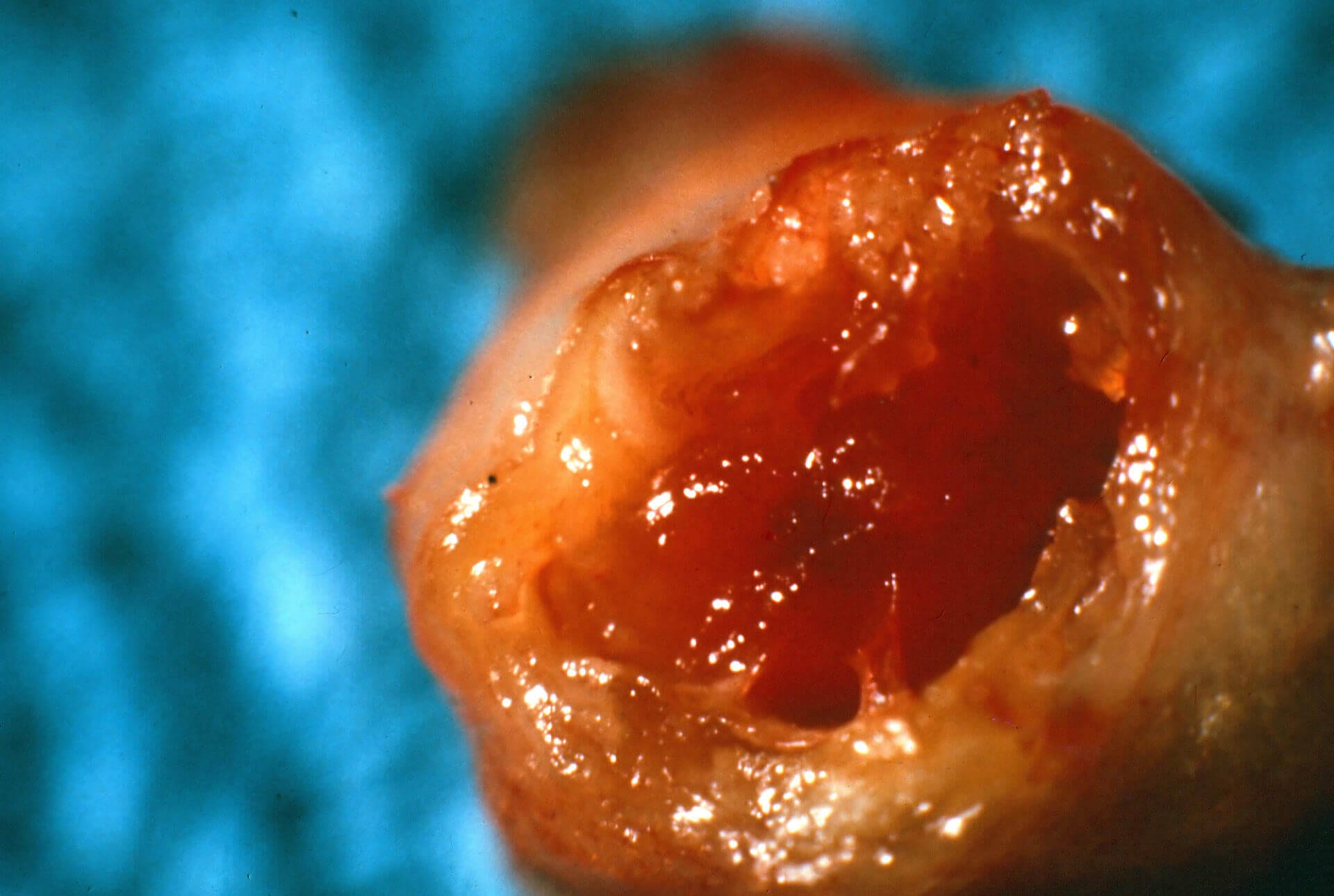

Additionally, we now know that the fat in clogged arteries is only about 26% saturated. The rest is unsaturated, of which more than half is polyunsaturated. One study concluded that polyunsaturated fatty acids tend to stick faster to atherosclerotic plaque, probably due to their higher susceptibility to oxidative modification.

I’ll explain in more detail below how arterial plaque forms and what you can do to prevent it. Hint: It doesn’t involve removing saturated fats from your diet.

Monounsaturated Fat

Monounsaturated fatty acids feature a double bond between two of the carbon molecules due to missing hydrogen atoms. Much like saturated fats, monounsaturated fats are relatively stable but their molecules don’t pack together as tightly as those of saturated fatty acids. As a result, most monounsaturated fats are liquid at room temperature.

Good sources of liquid monounsaturated fats include olive oil and avocado oil, and the most common monounsaturated fatty acid from dietary sources is oleic acid.

Considering their relative stability and presence in food that humans have consumed through evolution (e.g., meat), I have no concerns about making monounsaturated fatty acids a regular part of my diet.

Polyunsaturated Fat

Source: Cate Shanahan, MD (https://drcate.com/hateful-eight/)

Polyunsaturated fatty acids have two or more double bonds and exist in several types, including omega-3, omega-6 and omega-9 fatty acids.

Linoleic acid is the shortest chain of the common omega-6 fatty acids. It’s arguably also the worst of them because it has been shown in several studies to induce both obesity and cell death in the heart muscle as well as non-alcohol-induced liver disease.

The problem with PUFAs is that their double bonds are inherently less stable and more prone to oxidation than the single bonds in saturated fats. In other words, saturated fats retain their chemical structure much better when exposed to heat, oxygen, moisture or chemical reactions inside of the body.

That’s why you should never heat PUFAs or expose them to air or moisture. In other words, don’t use PUFAs for cooking or store them in airtight containers.

Oxidation refers to a transfer of electrons and a change in the chemical structure. A great example is when iron oxidizes by losing an electron, resulting in rust.

When an unsaturated fatty acid oxidizes, it leads to the creation of inflammatory compounds and, in turn, can lead to tissue damage, arteriosclerosis (the buildup of plaque inside artery walls), the accumulation of adipose (fat) tissue and a host of chronic diseases including cardiovascular disease, Type 2 diabetes, obesity and more.

The mechanism by which linoleic acid and other PUFAs cause health issues is well understood.

When these fats oxidize or become rancid, free radicals form. Free radicals are highly reactive atoms because they have an unpaired electron in the outer orbit.

Due to their tendency to react with other atoms, free radicals cause damage in DNA/RNA strands (also known as oxidative stress) leading to premature aging, tumors, the buildup of plaque, and autoimmune diseases such as arthritis and Alzheimer’s (among others).

Substituting dietary linoleic acid in place of saturated fats increased the rates of death from all causes, including coronary heart disease and cardiovascular disease.

— Sydney Heart Study

However, it’s worth noting that scientists recently discovered that your genetic makeup can influence the degree to which your body responds to linoleic acid with inflammation. In other words, the consequences of consuming excess amounts of linoleic acid might be worse for some people than others.

The consumption of linoleic acid also causes hyperphagia — the medical term for excessive hunger. This is likely the reason why you can’t eat just five potato chips (which are fried in seed oils), emptying the entire bag instead.

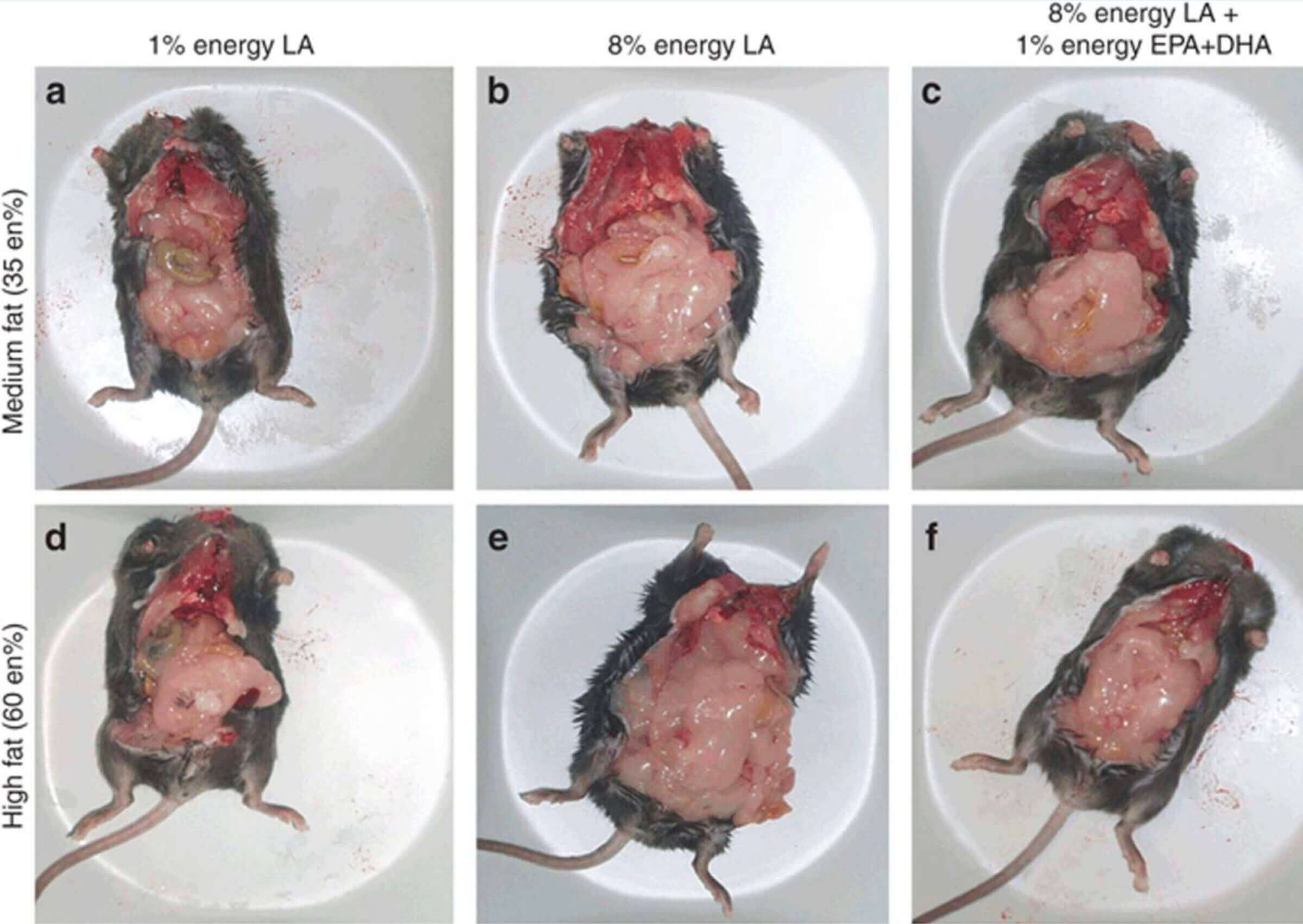

Just look at the above picture of mice that were fed different amounts of linoleic acid. The differences speak for themselves.

The reason why both mice and humans gain fat when consuming high amounts of linoleic acid is that it disrupts the endocannabinoid system in the hypothalamus, along with certain hunger hormones (including leptin).

Here’s the thing: many PUFAs are essential. That means the body can’t make them and, as such, we have to get them from the food we eat.

PUFAs are important for nerve function, blood clotting, brain health and other vital functions in the body. However, from an evolutionary perspective (and from observing modern hunter-gatherer tribes), it’s evident that Western diets include significantly higher amounts of PUFAs than humans should be consuming.

In other words, we should be getting about 4% of our calories from PUFAs, but modern diets contain as much as 30% from industrial seed oils derived mostly from soy, corn, safflower and canola. So it’s not that PUFAs are inherently bad, we just consume way too much of them.

Omega-3 vs. Omega-6

As you might have heard, omega-3 is supposed to be a healthy type of fat. However, it’s also a PUFA and is, thus, prone to oxidation. So you might be wondering why omega-3 is good and omega-6 is bad.

It’s true that heat, moisture and oxygen can destroy omega-3 fatty acids and make them rancid. That’s why you should never heat oils that are high in omega-3, and why many fish oil supplements aren’t as healthy as you might think; their oil has oxidized before you purchase the bottle.

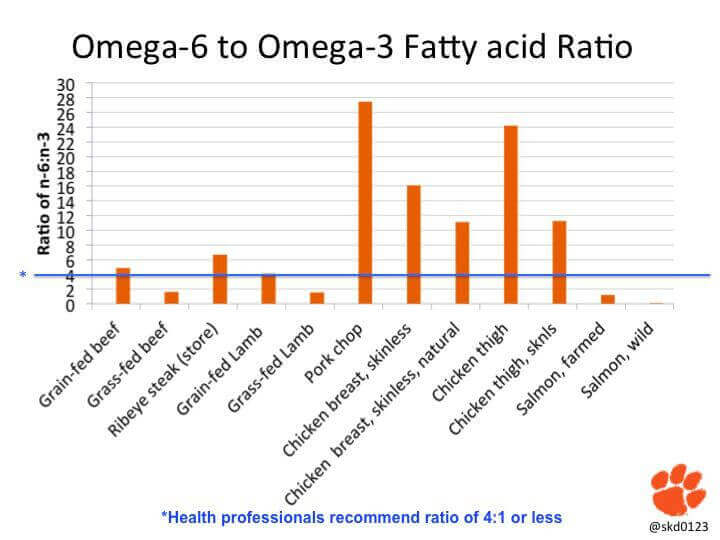

However, it’s proven that omega-3 fatty acids have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that protect other PUFAs, such as omega-6, from oxidizing. That’s one of the reasons why it’s important to maintain an evolutionary consistent ratio of approximately 1:1 as far as your intake of omega-3 vs. omega-6 is concerned.

In other words, you should consume as much omega-3 as you do omega-6 — ideally from whole-food sources (not processed oils or supplements).

Don’t cook with soybean oil and then supplement with fish oil in an attempt to balance out your omega-3 to omega-6 ratio. Instead, remove the most prevalent sources of inflammatory omega-6 fatty acids from your diet, including vegetable oil, meat from monogastric animals (like chicken and pork) and nut butter.

If you do that while also consuming foods that are high in omega-3 (such as oily fish like salmon and sardines), you won’t have to worry about your omega-3 to omega-6 ratio.

Trans Fat

In nature, trans fats are created in the digestive tract of ruminants when bacteria add hydrogen atoms to polyunsaturated fatty acids from the food the animal has eaten. One example is conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), a trans fat found in ruminant animals like cows and horses. Unlike trans fats in industrial seed oils, CLA is harmless, as several studies have shown.

That shouldn’t really come as a surprise because humans evolved by consuming animal meat and fat without developing health issues.

The real problem is industrially-made trans fats that manufacturers create when chemically altering liquid vegetable oils to make them solid at room temperature (and thus shelf-stable).

These trans fats — which are often found in margarine and other highly-processed foods — negatively impact insulin sensitivity (increasing your risk of developing diabetes), cause the oxidation of low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and lead to other health issues. The latter is a major driver for cardiovascular disease and arterial plaque.

Unfortunately, many of the studies linked to above that investigated the consumption of trans fats on health markers are observational. In other words, they establish a correlation but they don’t prove causation.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not defending trans fats or suggesting you make them a regular part of your diet. However, the body can evidently (as proven by evolution) handle small amounts of trans fats, such as the ones present in meat.

But once you overload the body’s natural defense mechanisms by maintaining a diet that’s low in antioxidants paired with the consumption of highly-processed foods that contain inflammatory trans fats, you have a problem.

Speaking of products containing trans fats: in 2018, the FDA partially banned trans fats in most (but not all) products. However, manufacturers are still allowed to label products as “free of trans fats” if they contain less than 0.5 grams of trans fat per serving. Imagine a box of crackers or cookies, each containing 0.5 grams of this fat. That adds up quickly!

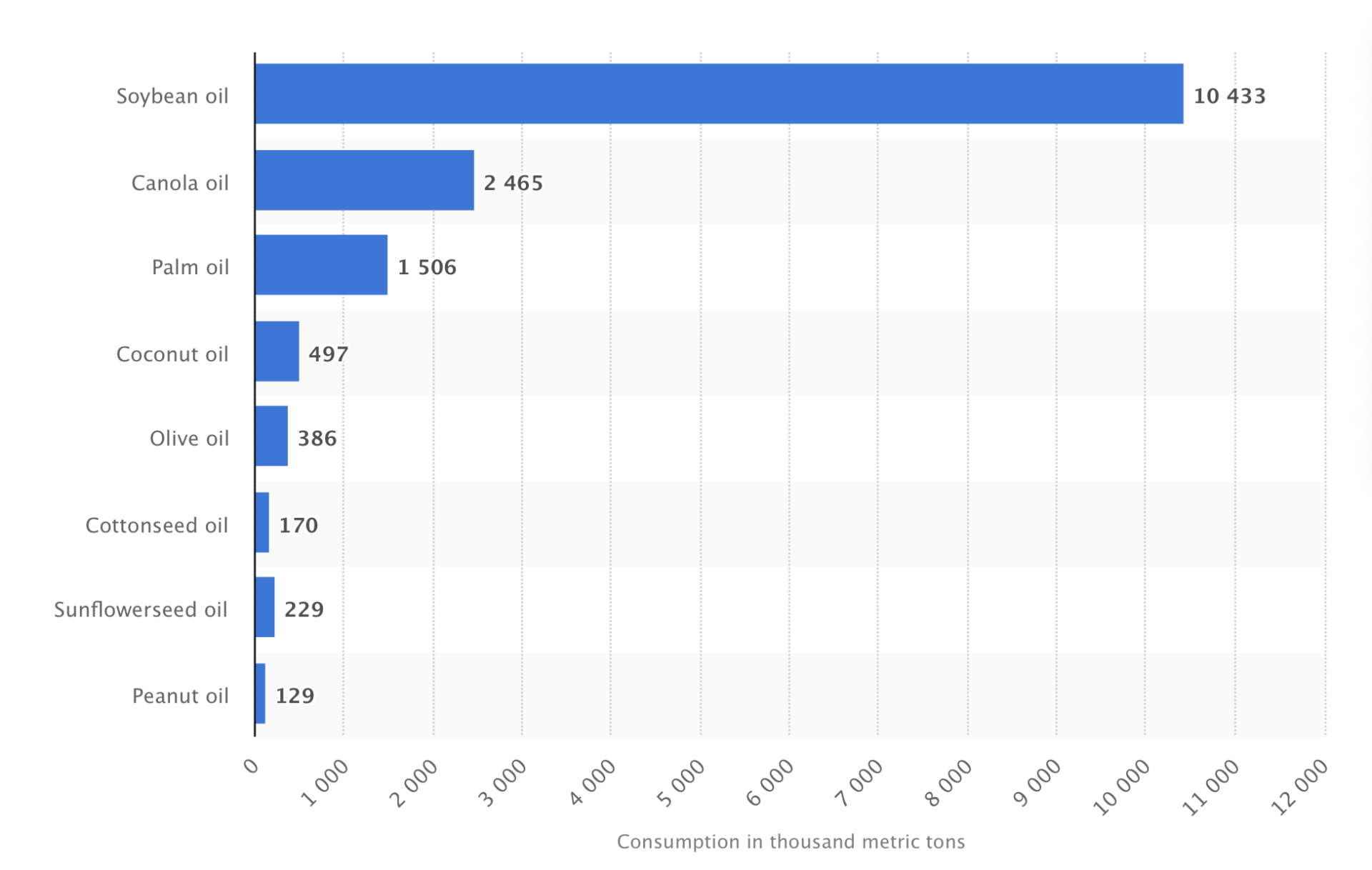

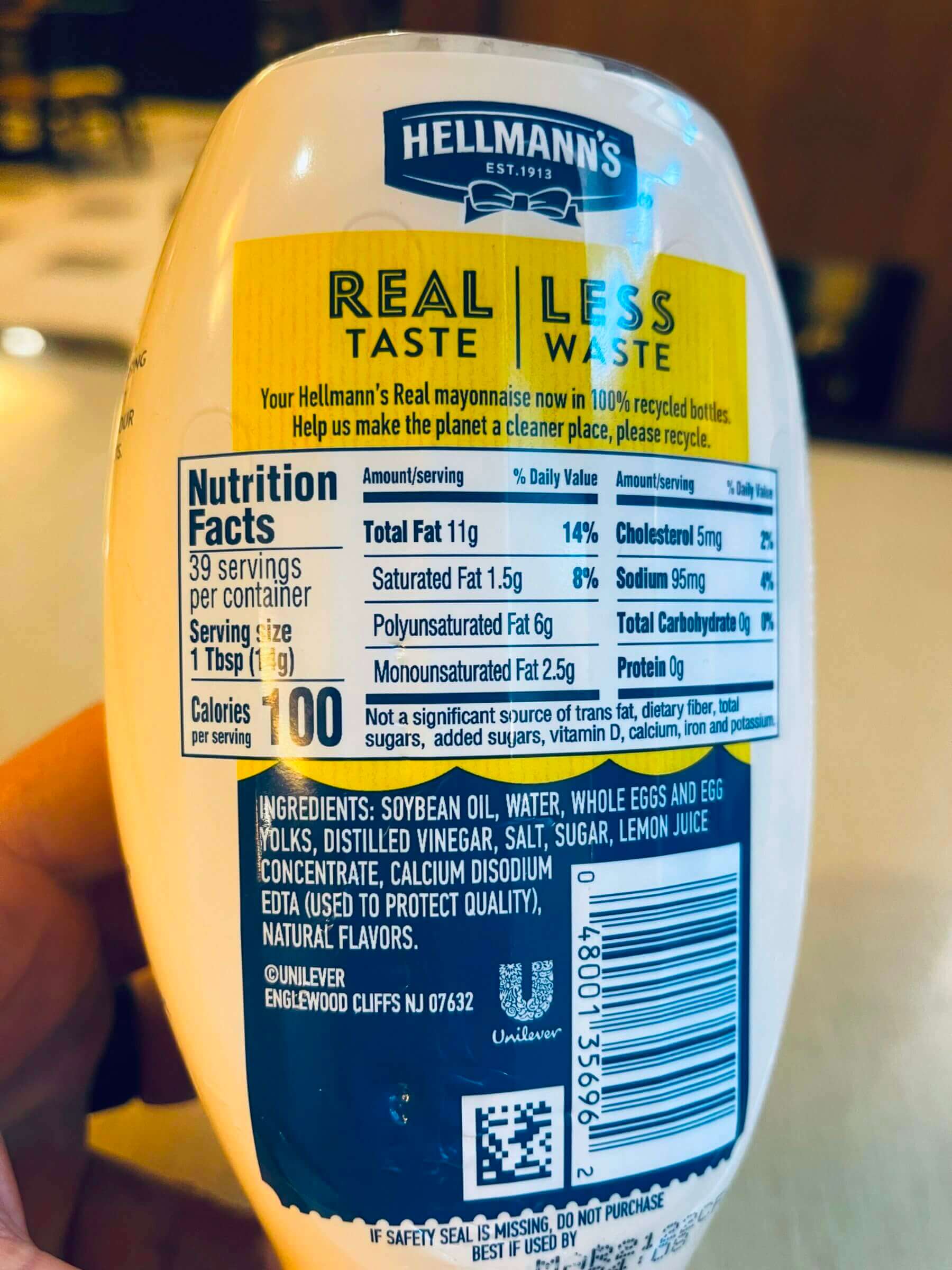

Additionally, many vegetable oils, including soybean oil, contain between 0.56% and 4.2% trans fats. So by using soybean oil you get the double whammy of linoleic acid and trans fats!

Fortunately, the solution to avoiding such hidden trans fats is simple: stay away from shelf-stable processed foods, don’t cook with vegetable oils, and avoid fried foods in restaurants.

Foods That Are High in Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids

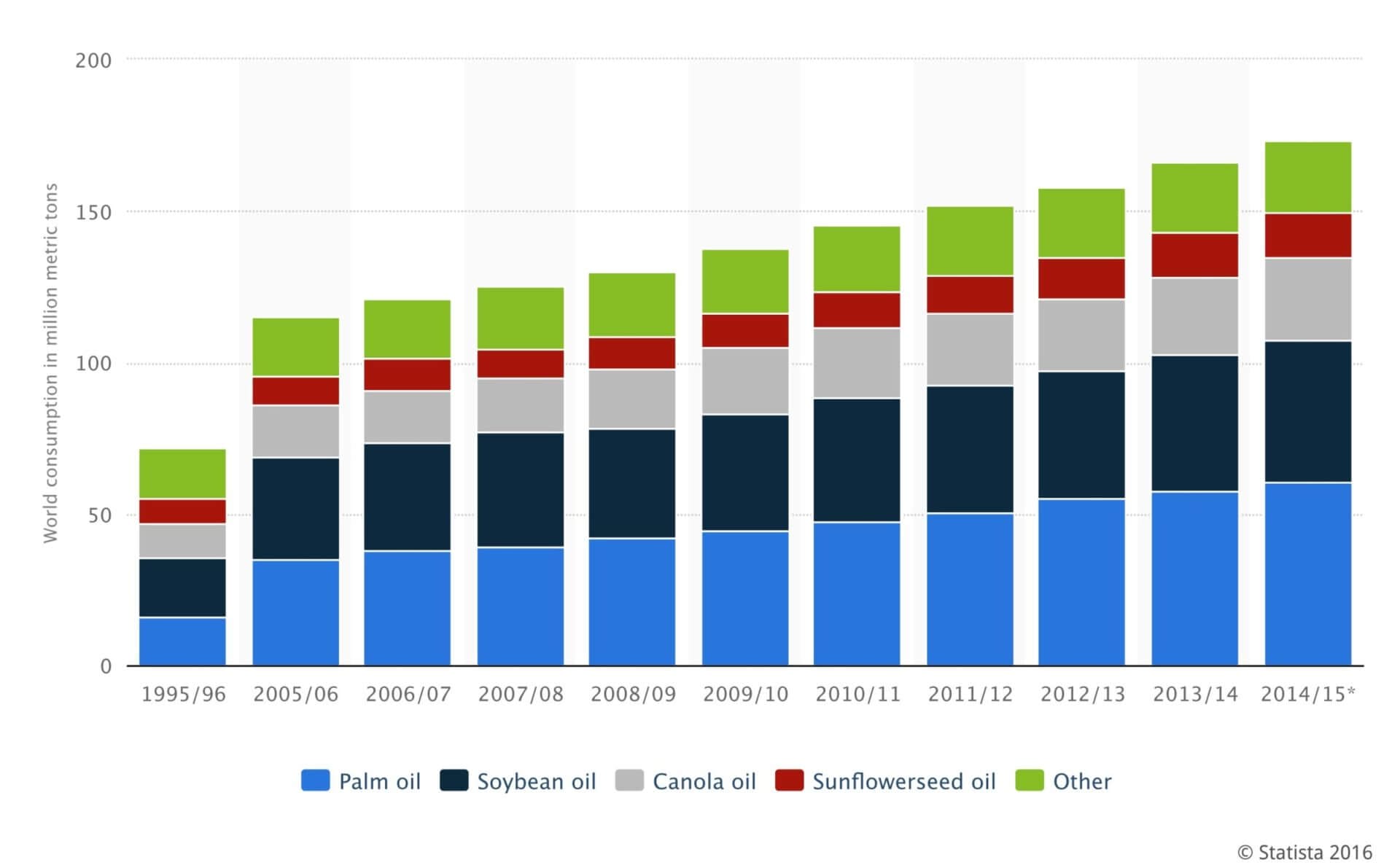

Arguably the most prevalent sources of dietary PUFAs are industrial seed oils (also known as vegetable oils). So here’s a list of popular cooking oils that I highly recommend you stay away from:

- Almond oil

- Apricot kernel oil

- Canola oil

- Corn oil

- Cottonseed oil

- Grape seed oil

- Hazelnut oil

- Mustard seed oil

- Oat oil

- Palm oil

- Peanut oil

- Rice bran oil

- Safflower oil

- Sesame oil

- Soybean oil

- Sunflower oil

The reasons why these oils are so harmful are that they contain incredibly high concentrations of omega-6 (i.e., linoleic acid), have little or no (protective) omega-3 fatty acids, are manufactured using high heat (which causes oxidation and rancidity) or harsh chemicals (e.g., hexane), or are subject to a combination of these factors.

But even if you avoid using these oils for cooking at home, you’ll likely get exposed to them on a regular basis, if you’re not careful. For example, pretty much all restaurants fry their food in vegetable oils because they’re so inexpensive.

Even worse, I bet that most restaurants don’t change the oil in their fryers on a daily basis, choosing to just top it off instead. As a result, your beloved french fries are likely fried in largely oxidized and rancid soybean oil that inflicts massive damage on your body.

Additionally, many packaged foods — such as crackers, margarine or salad dressings — include the harmful oils I mentioned above.

As a result, you have to be vigilant and extremely careful if you want to avoid omega-6 fatty acids.

Omega-6 in Pork and Poultry

But what about PUFAs found in the meat of monogastric animals (e.g., pork or chicken), grains, legumes, nuts or seeds?

It’s true that most pork and chicken is also relatively high in these inflammatory omega-6 fatty acids (compared to the meat of grass-fed ruminants) because of the soy and corn-based diet commercial farms feed these animals, and because of the fact that monogastric animals can’t convert PUFAs from their diet to saturated fats (like ruminants can).

Most large animals, especially ruminants, are rich sources of saturated fatty acids because their stomachs convert plant lipids to saturated fatty acids in a process called lipolysis.

As a result, I recommend consuming predominantly meat from ruminant animals, such as cattle, goats, sheep, buffalo, bison and deer, instead of that from monogastric animals like pigs, chickens, ducks and turkeys. However, if you choose to include pork or chicken in your diet (like I do), I recommend looking for pasture-raised options because those animals have much lower concentrations of omega-6 in their fat.

Unfortunately, pasture-raised chicken is ridiculously expensive in this country. We usually pay over $30 for a whole chicken. That’s nuts, and the reason why we’re considering adding “meat birds” to our Kummer Homestead next year (we already have a flock of egg-laying chickens).

As far as seeds and grains are concerned, I try to avoid them as much as possible for all the reasons I explained in my plants vs. meat article. In a nutshell (pun intended), most nuts and seeds have a lot of omega-6 that can easily go rancid when these products are exposed to heat (such as during roasting), moisture or air (during storage).

Check out this article to learn more about the best nuts and seeds based on their omega-3 to omega-6 ratio.

From that perspective, eating nuts and seeds raw might sound like a good idea. However, by eating them raw you ingest all of their anti-nutrients, which will wreak havoc on your GI tract.

Roasting them destroys many of these chemical defense toxins but also damages their PUFAs. In other words, you lose either way. The same principle applies to grains and legumes, which is why I’ve largely removed them from my diet.

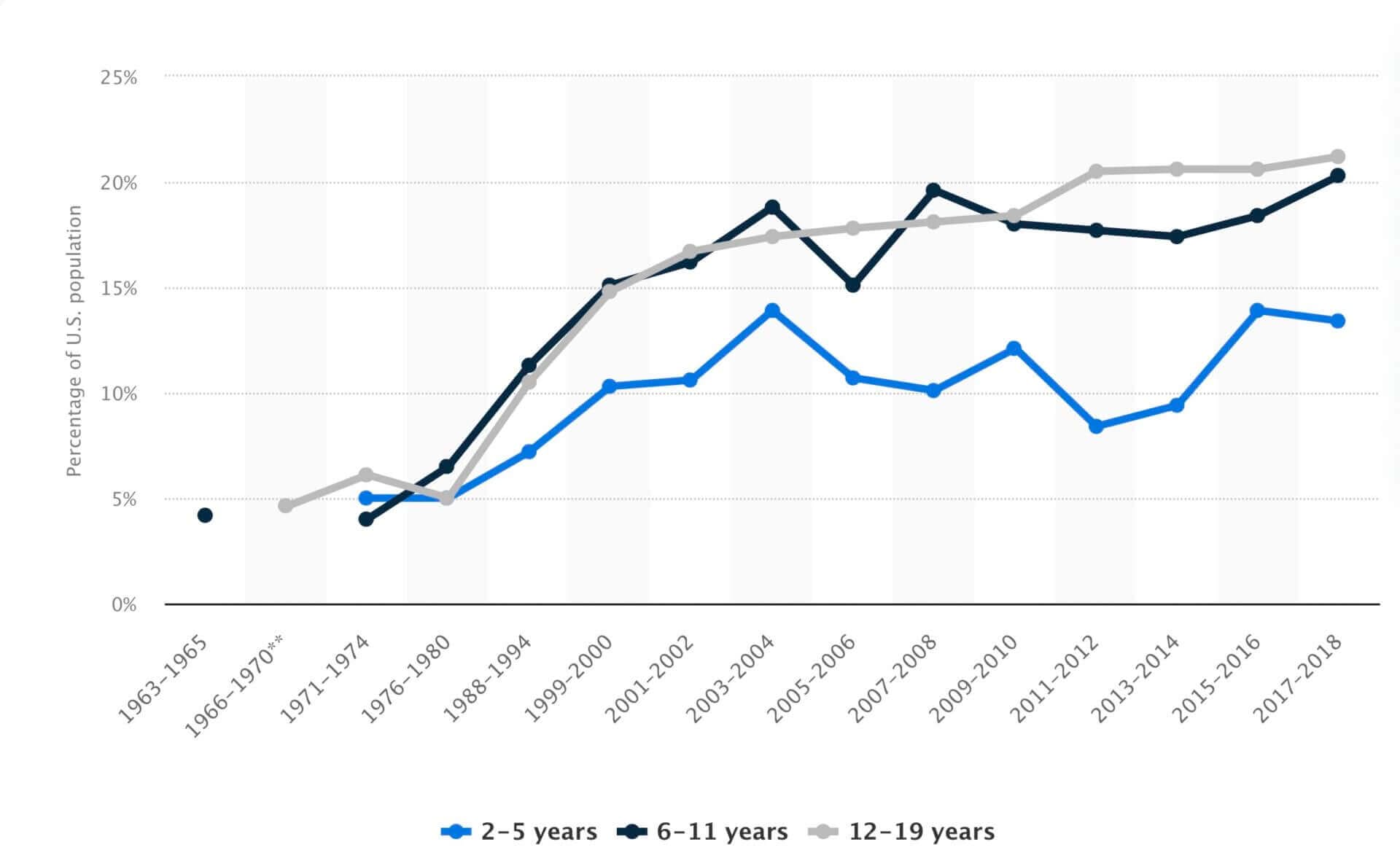

How Fat Consumption Has Changed Over Time

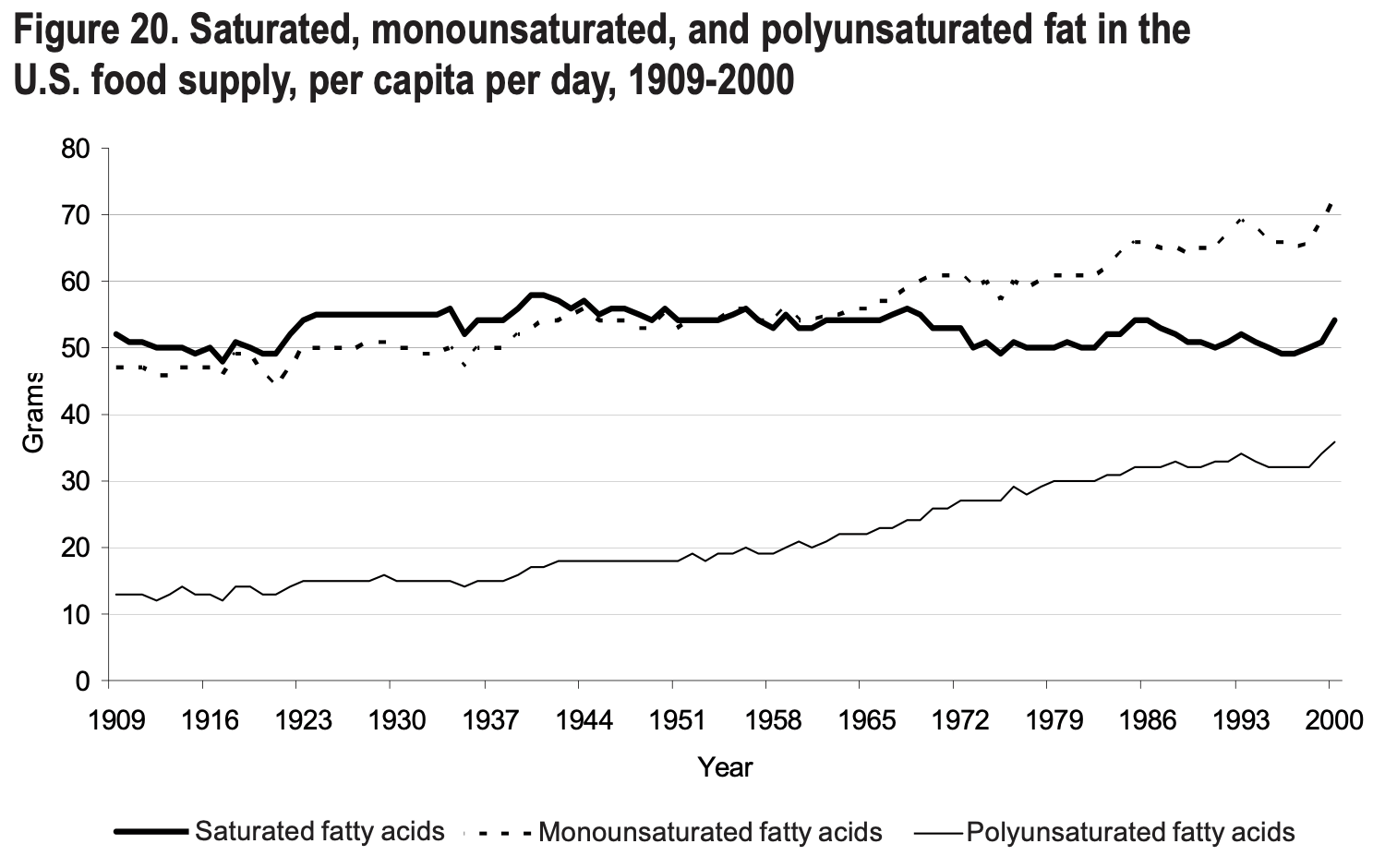

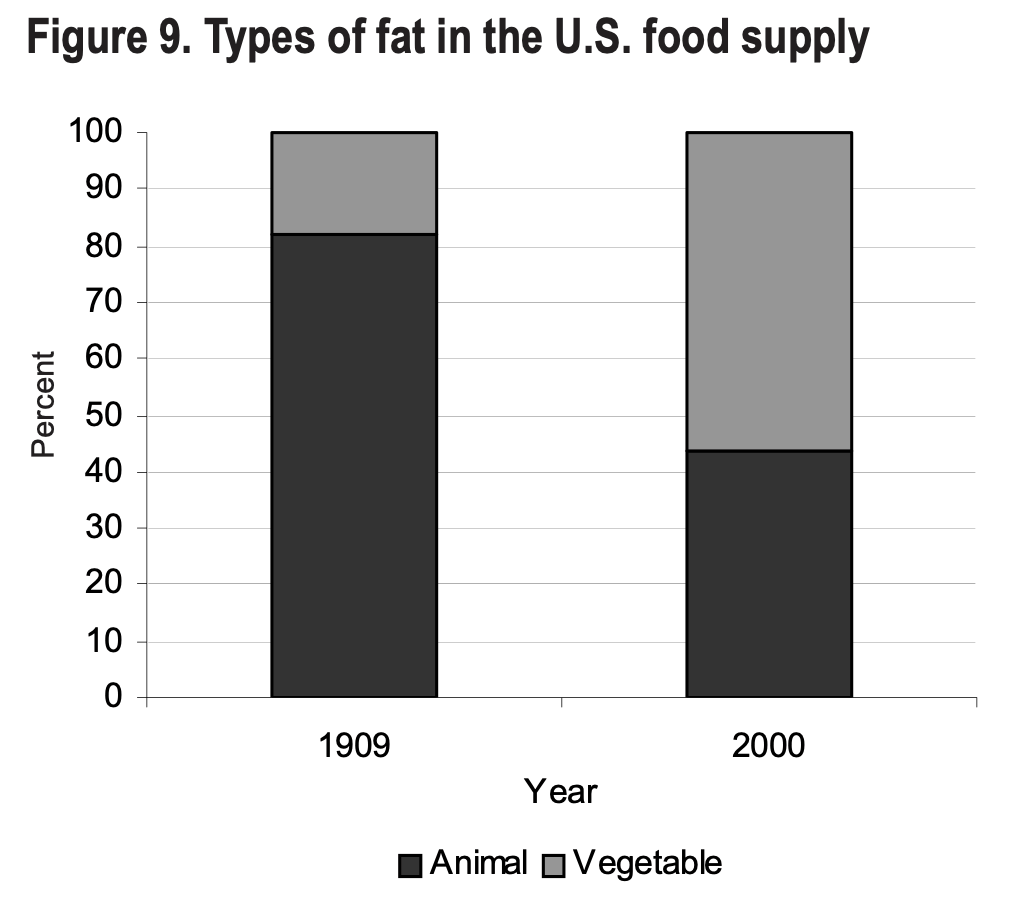

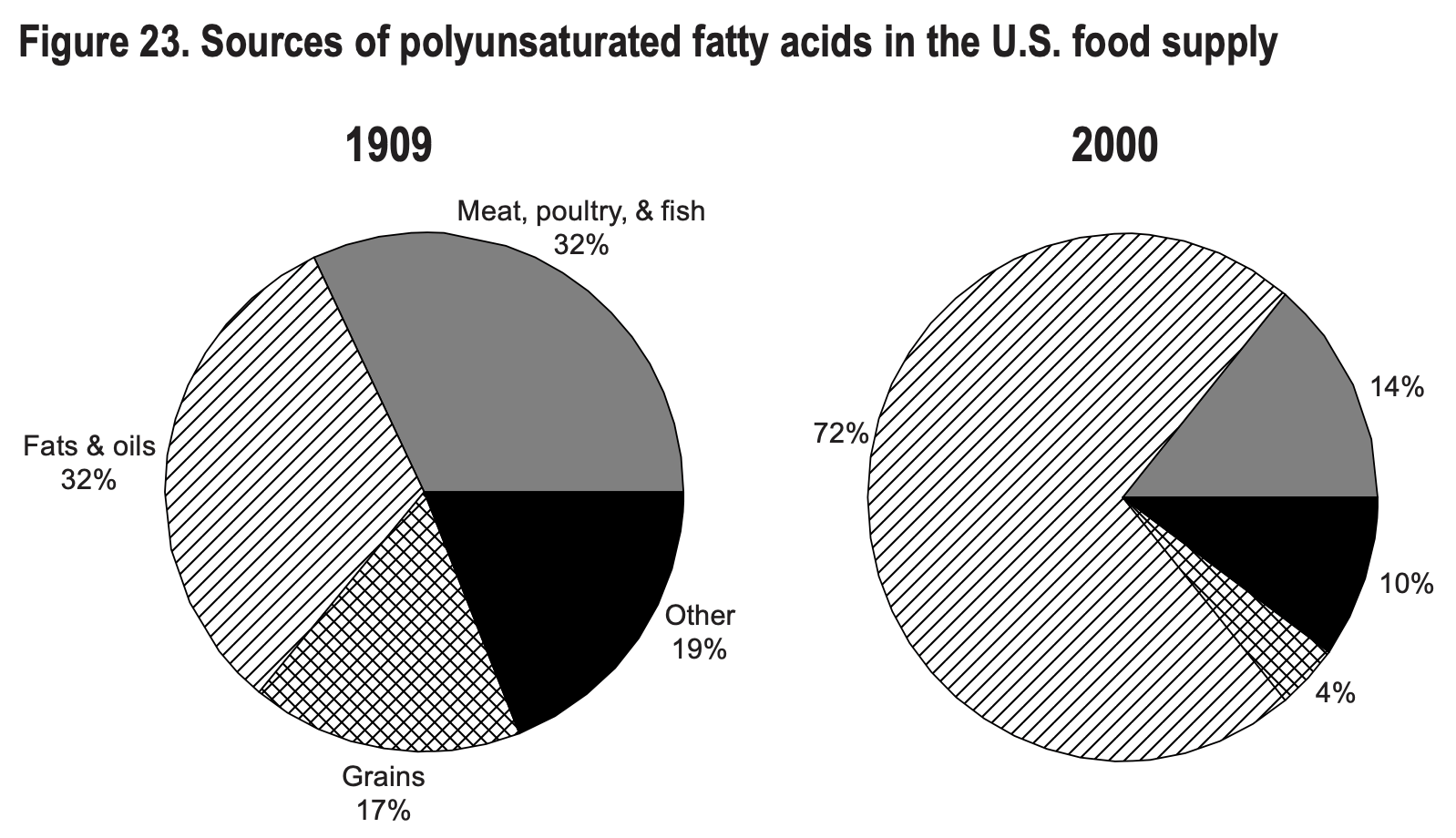

Throughout this article, I’ve mentioned that consuming high amounts of PUFAs is evolutionarily inconsistent because humans have predominantly relied on saturated and monounsaturated fats for millions of years.

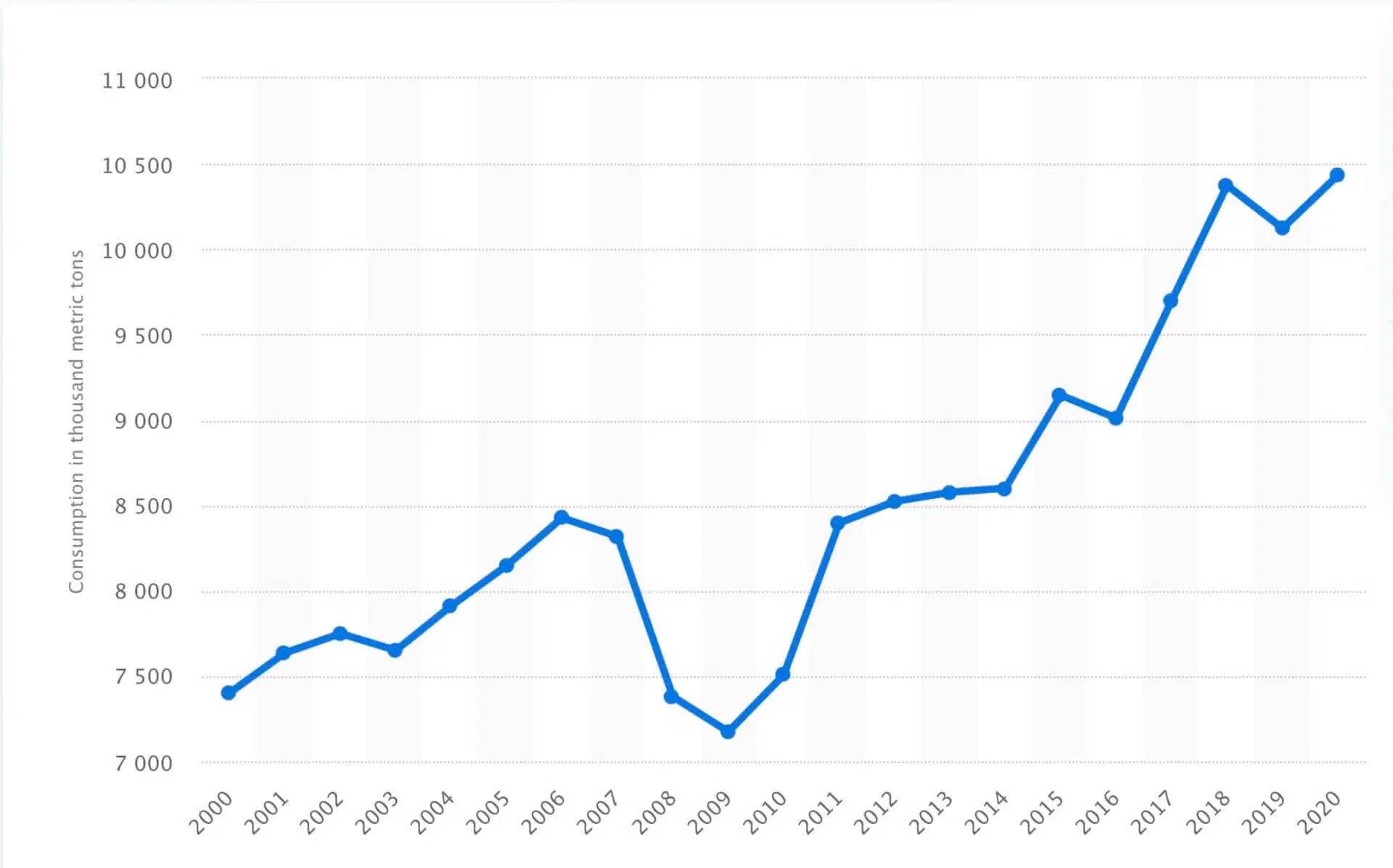

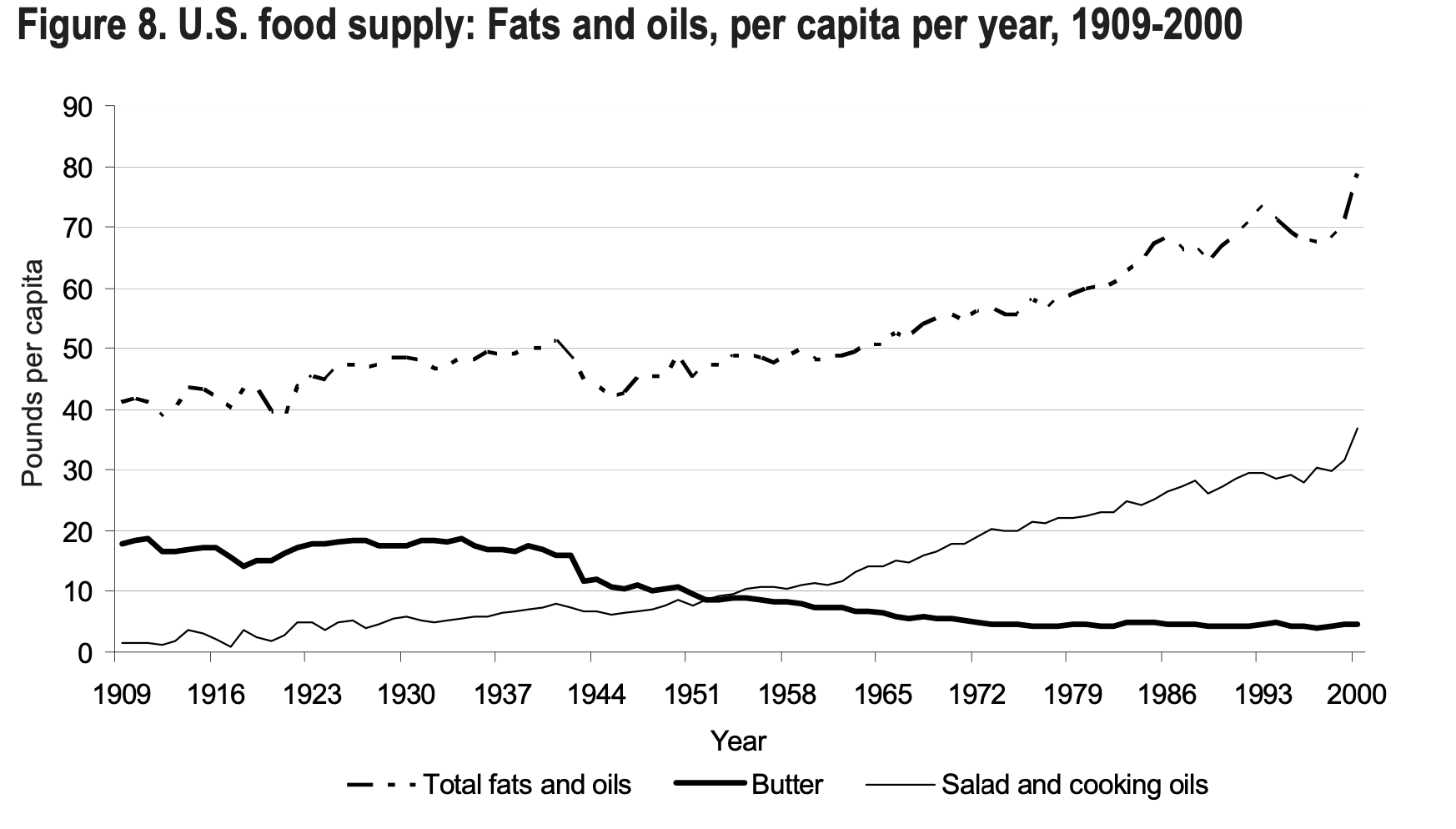

I discuss this issue in more detail in my article comparing meat vs. plants, so I won’t repeat everything I say in that post. However, I do want to take the opportunity to discuss how our eating patterns (as far as fat is concerned) have changed over the last century, and how that change correlates with rates of chronic diseases like obesity, diabetes and heart disease.

On a side note, if you have grandparents, ask them what type of fat they used for cooking when they were younger. I bet their answer will be butter, lard or tallow — two great sources of saturated fats.

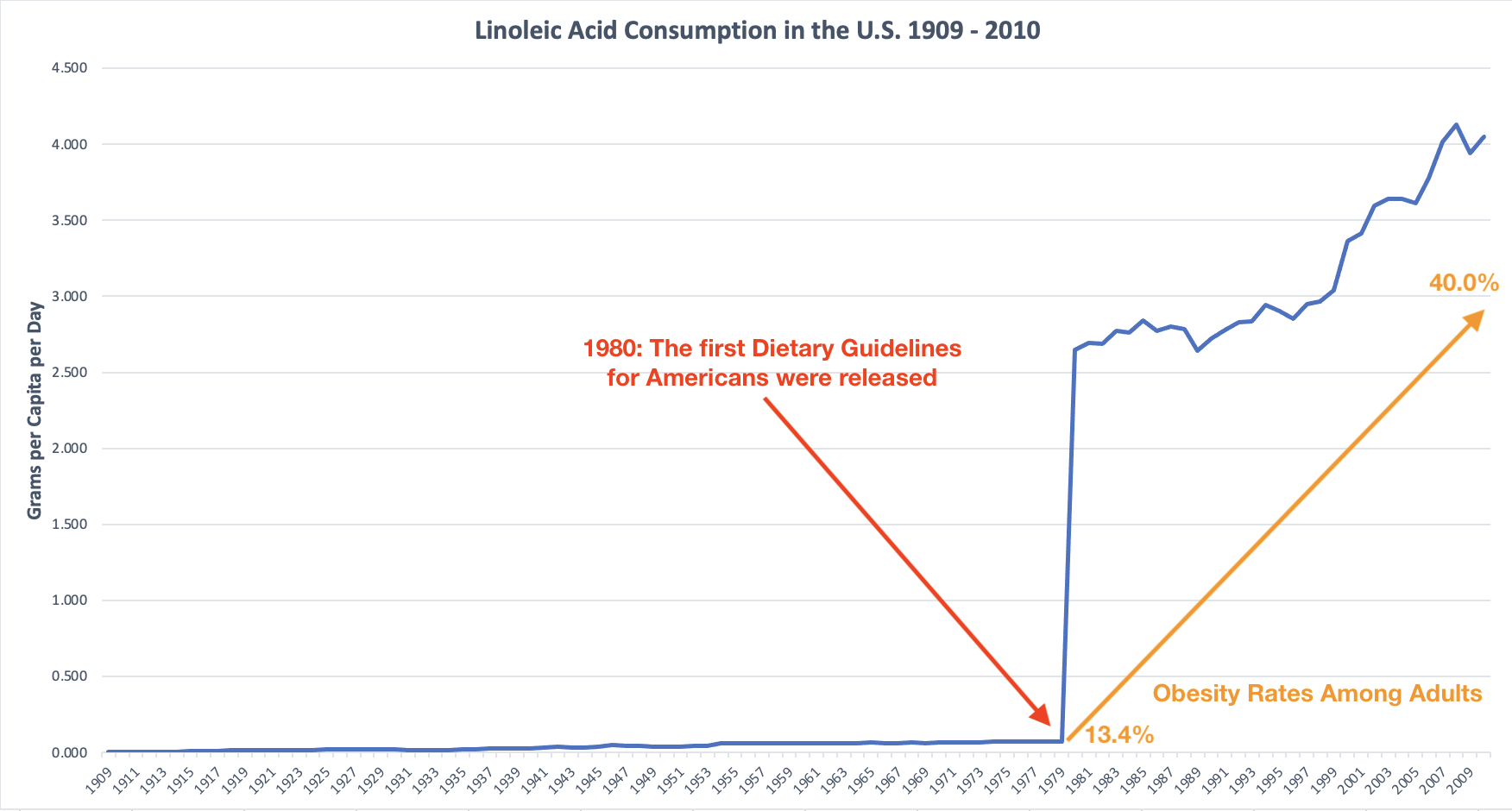

Let’s start by looking at the most striking correlation between fatty acid intake and obesity prevalence in the United States.

As you can see in the graph I put together based on statistics from the USDA and CDC, our intake of linoleic acid started to skyrocket with the introduction of the first Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

Coincidentally, obesity rates started to increase at approximately the same pace, while the overall consumption of carbohydrates increased slightly, too.

I’m sure you can guess where all of that linoleic acid was suddenly coming from: industrial seed oils, and soybean oil in particular.

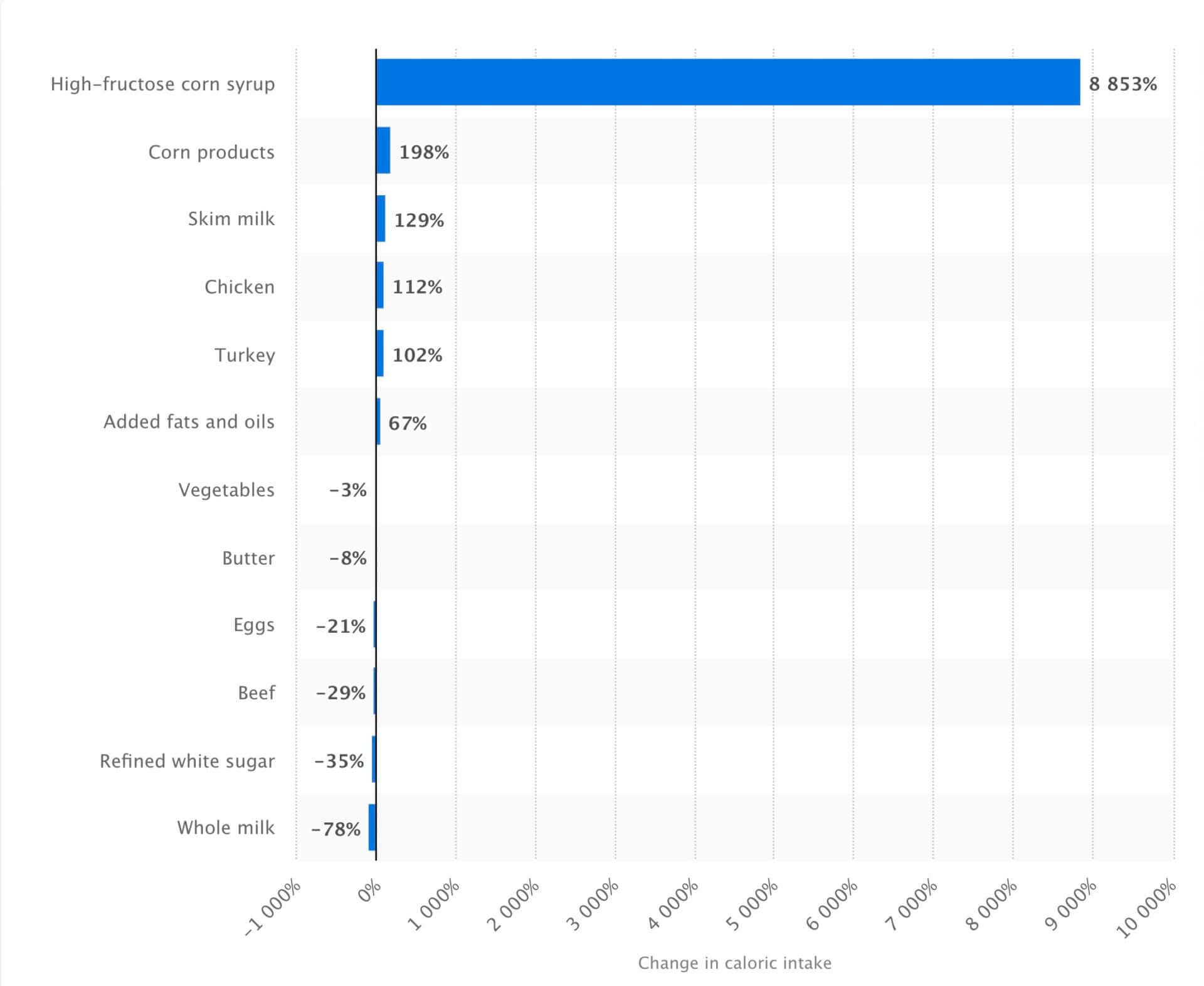

What’s interesting is that the consumption of refined sugars has declined over the past few decades, as you can see in the image below. But guess what food manufacturers replaced sugar with: high-fructose corn syrup, another highly-inflammatory sweetener that’s prominent in many processed foods and drinks.

To put all of this into context, let’s look at incident rates for cardiovascular disease over the last century.

In 1900, cardiovascular disease was a rare occurrence in the United States. Only ~27,427 deaths were due to the condition, according to the CDC.

By the middle of the 20th century, cardiovascular disease had become more widespread, and the so-called lipid hypothesis garnered greater attention. The lipid hypothesis suggested a direct connection between the consumption of fat (specifically, saturated fat) and heart disease.

Interestingly enough, however, is the fact that while the number of deaths due to heart disease increased drastically, the proportion of animal fat in the American diet declined from 83% to 62%, and butter consumption plummeted. In parallel, the consumption of refined vegetable oils dramatically increased, as demonstrated above.

Approximately 85.6 million Americans suffer from some form of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and close to 1 in 3 deaths result from CVD. These are not only deadly but costly diseases with CVD and stroke costing around $320 billion each year.

— Rosamond W, Flegal K, Furie K, Go A, et al.

So if saturated fats were the primary cause of heart disease, then a decline in saturated fat consumption should have led to a decline in cardiovascular disease as well. But it didn’t. In fact, the opposite was the case!

So evidently, the consumption of saturated fats doesn’t cause heart disease. But based on the overwhelming scientific evidence, it’s safe to assume that industrial seed oils, paired with processed carbohydrates, are ruining our health.

These days, most people in the United States die of heart disease or cancer. That’s unfortunate because, based on the scientific evidence we have available today, these are two preventable diseases that are caused by metabolic dysfunction and driven by the consumption of industrial seed oils (especially linoleic acid) and highly-processed carbohydrates.

How Saturated and Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Impact Blood Lipid Levels

Arguably the main reason why many people think that polyunsaturated fats are healthier than saturated fats is because of their impact on blood lipid levels. In other words, they’re concerned about the impact of saturated fats on their cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels.

On the flip side, some studies have shown that consuming predominantly polyunsaturated fats lowers LDL levels.

What most people — including, unfortunately, most healthcare professionals — don’t understand is that total cholesterol and LDL are incredibly unreliable indicators of cardiovascular risk.

Getting into the nitty-gritty of blood lipid markers and cardiovascular disease would require an entirely new article, so I’ll try to keep it brief.

The bottom line is that LDL isn’t bad cholesterol. In fact, it’s not cholesterol (or fat) at all. It’s a protein (as its name suggests) that transports cholesterol to where it’s needed in the body. So it’s super important and you couldn’t live without it. The more fat you consume (e.g., if you’re on a high-fat or ketogenic diet), the more cholesterol you’ll have in your bloodstream and the more LDL you need to transport it.

That’s why many people who follow a ketogenic diet have “higher than normal” blood lipid markers.

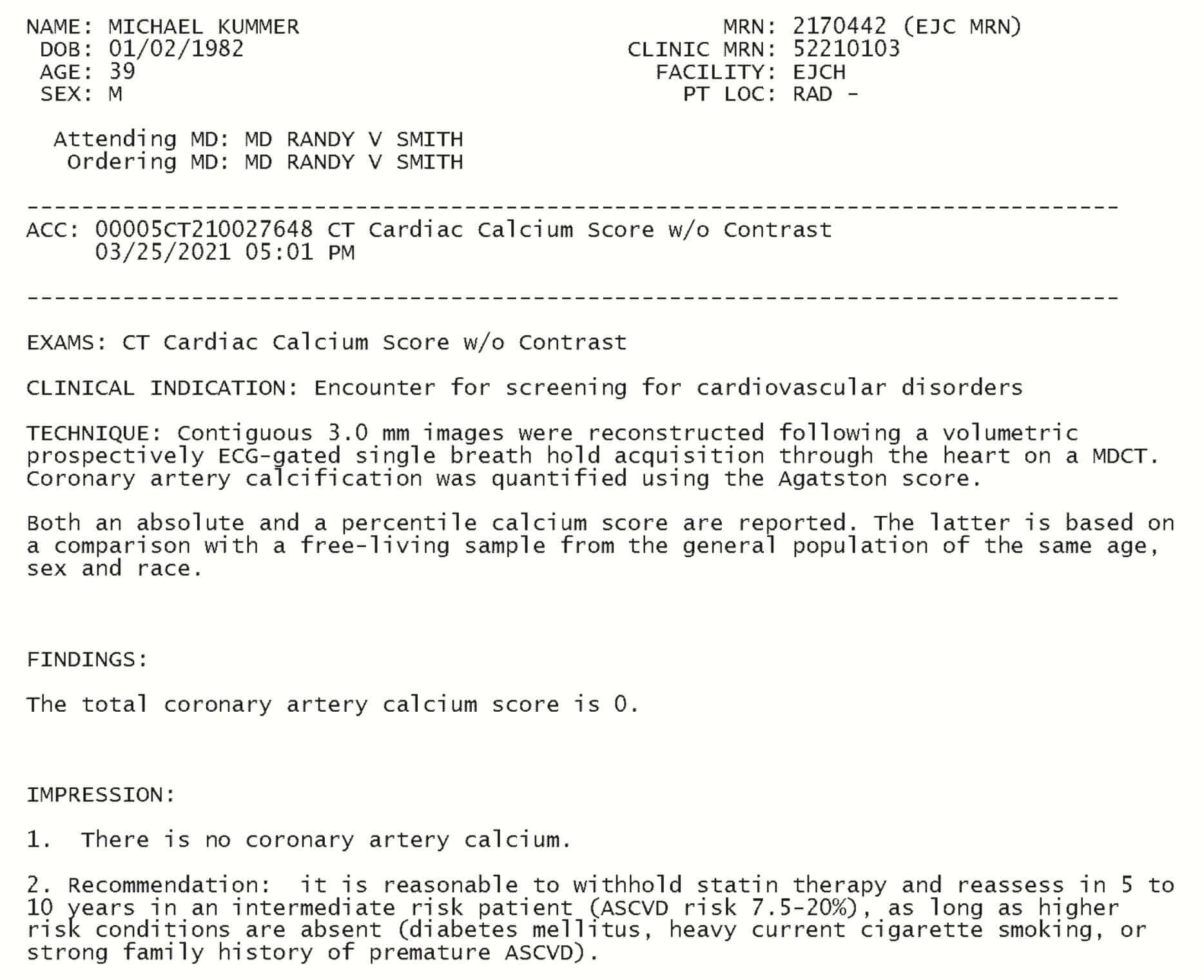

My cholesterol and LDL levels are usually way above the “normal” range (244 and 180, respectively). Yet all of my inflammatory markers are extremely low (CRP < 0.3) and I show zero signs of arterial plaque (as confirmed by a recent calcium score test).

High c-reactive protein (CRP) levels are a good indicator of oxidized LDL (OxLDL).

How is that possible?

It’s possible because LDL only becomes an issue when it oxidizes. And how does it oxidize? When you consume a diet that’s high in inflammatory polyunsaturated fats (that oxidize readily) and processed carbs.

On the flip side, you can actually have low LDL numbers with high ratios of oxidized LDL as demonstrated by this paper. In other words, a “heart-healthy” diet consisting of vegetable oils and morning cereals increases your risk of cardiovascular disease dramatically, while a diet high in saturated fat (like the ketogenic diet) lowers that risk.

That’s why I largely ignore my total cholesterol and LDL numbers and only look at my triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), CRP and LP(a) numbers when I do my blood work.

If your triglycerides are low (mine are usually in the mid 40s), your HDL is high (mine is usually in the upper 40s) and your CRP is low (mine is always under 0.3), you can almost be certain that you don’t have oxidized LDL.

To confirm, you can do an LDL particle scan that identifies what type of LDL particles you have in your bloodstream. I did that and it confirmed that my LDL is perfectly healthy (not oxidized) and doesn’t cause any arterial plaque.

On a side note, having elevated triglycerides means that your body is converting unused energy (from the food you eat) and storing it as fat. As a result, consistently high triglycerides mean that you’re overeating or consuming too much of the wrong food (likely carbs). That leads to insulin resistance, and it ultimately increases your risk of cardiovascular disease.

The bottom line is that saturated fats aren’t bad simply because they might increase certain blood lipid markers, and polyunsaturated fats aren’t good simply because they lower LDL. Both views are naive takes on the subject that fail to account for how the body really works.

Frequently Asked Questions

No, fortunately, it doesn’t. The omega-3 PUFAs are protected from heat by the proteins and antioxidants found in salmon. Of course, that doesn’t mean you should grill salmon over 1,000 degrees until it’s dry; doing so will likely cause damage to certain fatty acids and heat-sensitive nutrients.

That’s why steaming and low-heat cooking are likely better options for foods that are high in PUFAs. I usually eat salmon medium-rare to further reduce the risk of damaged fatty acids.

Much like xenoestrogens, I don’t think you can completely avoid PUFAs in your diet. They’re just too prevalent. But you probably wouldn’t want to anyway, because omega-6 fatty acids play an important role in the human body, and are needed for proper nerve function, blood clotting and other things as mentioned above. The goal should be to avoid consuming more omega-6 than your body is primed to handle, from an evolutionary perspective.

You can do that by cutting out vegetable oils and avoiding fried food in restaurants. If you want to take it even a step further, reduce your intake of foods that have higher amounts of PUFAs, such as nuts, seeds, commercial chicken and grain-fed pork.

We don’t eat out a lot, but when we do, I try to stay away from deep-fried foods. I also frequently ask what oils the chef uses to prepare meals. If I don’t like the answer, I ask them if they can use olive oil or butter instead.

If I travel for work, I bring my own oils in the form of Kasandrinos Extra Virgin Olive Oil or tallow we render at home.

On a side note, we recently found out that one of our favorite breakfast places offers grass-fed butter and so we got into the habit of asking them to use butter when frying our eggs instead of the PAM spray they normally use.

I recommend tallow (rendered beef fat), grass-fed butter or coconut oil. Occasionally, we also use high-quality olive and avocado oil. The problem with the latter oils is that they’re often not pure and/or rancid. So make sure you buy them from a trusted brand. We use Kasandrinos for the most part.

You can check out this article to learn more about the best cooking oils.

There’s a lot of observational evidence that suggests that saturated fats impair calcium absorption in the gut, and thus increase your risk of osteoporosis. But such statements are as misleading as saying that you have to drink milk (or consume dairy) to maintain healthy bones.

While some studies have linked saturated fats to reduced calcium absorption, others have shown the opposite effect.

A review on the issue of dietary fat and calcium absorption published in the Royal Society of Chemistry clearly stated that, “Nevertheless, studies of dietary fat on passive Ca absorption are limited, and effects of HFD on CaB remain unknown.”

In other words, there is no credible scientific evidence to suggest that the type of fatty acids humans have consumed for millions of years adversely affects bone health.

What causes weak bones is nutritional deficiency due to poor dietary habits. And in particular, a diet that lacks sufficient amounts of vitamin D3 and vitamin K2.

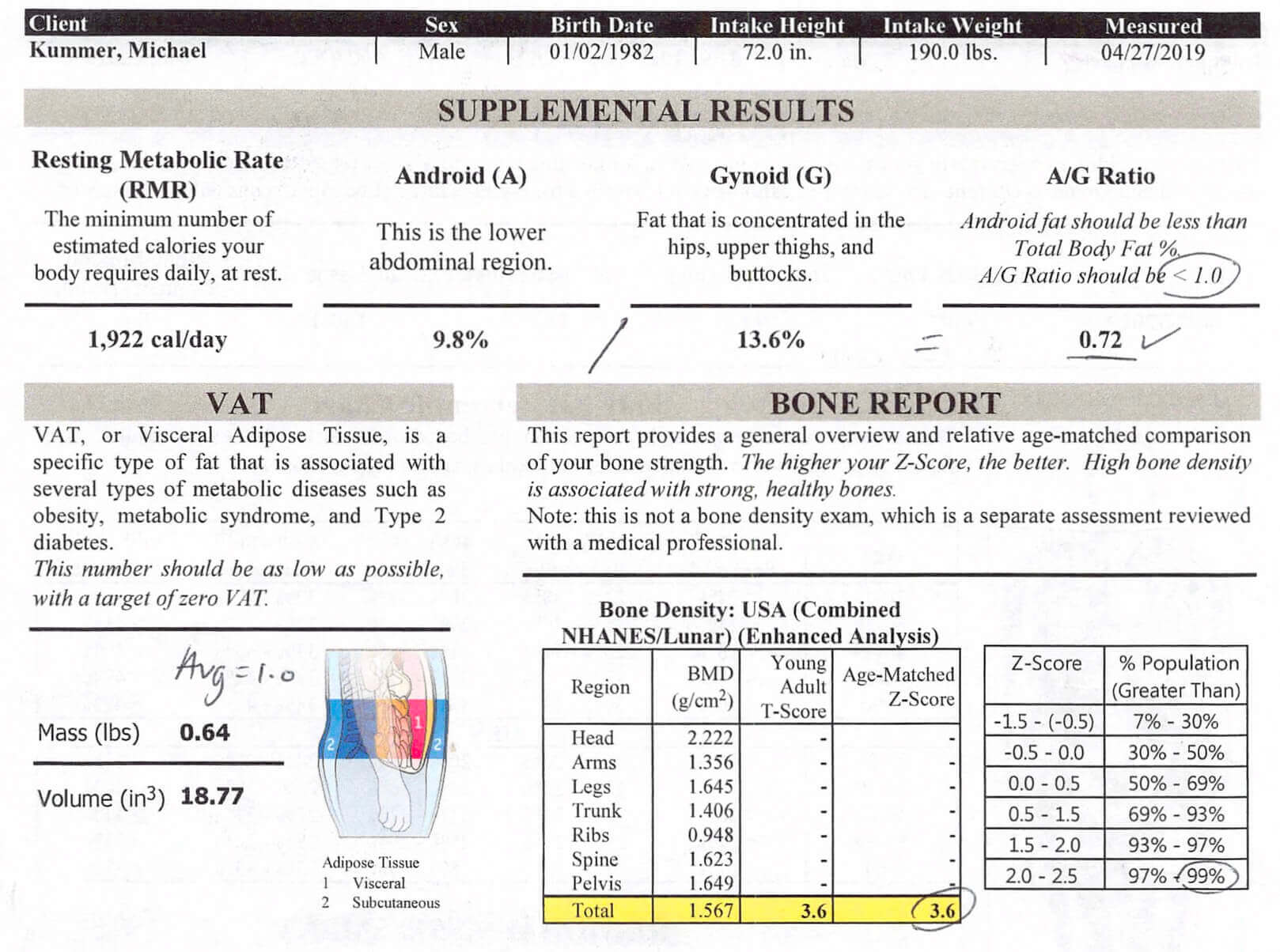

I recently had a bone density scan done (see the image above) and it came back with a Z-score of 3.6, which is over 99% higher than the general population. So evidently, my evolutionarily consistent (high) intake of saturated fat doesn’t impact my body’s ability to absorb calcium in any way.

It’s true that fewer Americans are dying of CVD than 20 years ago. Unfortunately, that’s not a reason to celebrate, because the death rates from other metabolic disorders, such as cancer, are on the rise.

It’s important to understand that most modern diseases, including CVD, cancer, obesity, Alzheimer’s, diabetes and autoimmune conditions, have the same root cause: metabolic dysfunction stemming from poor lifestyle choices and, in particular, a diet high in omega-6 PUFAs and highly-processed carbs.

In other words, the death rates from all metabolic diseases haven’t declined, and we are no healthier today than we were 20 years ago. The opposite is the case. But perhaps modern medicine has managed to keep CVD patients alive longer so they die of other causes (like cancer or diabetes).

Attributing the lower death rates from CVD to the increase in the consumption of PUFAs while the overall death rates of metabolic diseases are skyrocketing is downright naive.

There are a couple of issues I’ve seen associated with studies on the health effects of different fatty acids. Well-designed studies incorporate a “lead-in” with one type of fatty acid before switching to the one they want to study.

For example, the mouse study I mentioned earlier in the article fed the mice saturated fats for a few weeks before testing the different amounts of linoleic acid. If you don’t incorporate such a lead-in, you might not get accurate results, because it might take the body a while to recover and for inflammatory markers to return to baseline after being fed unhealthy fats.

The other problem with linoleic acid and other PUFAs is that you likely won’t see benefits if you reduce the consumption by significant amounts. In other words, if you get 20% of your calories from PUFAs and then you reduce your intake to 15%, you likely won’t see any positive effects because you’re still way above the threshold of what your body can handle.

To see a difference, you have to reduce your intake to levels that are consistent with what the human body can handle from an evolutionary perspective. As a rule of thumb, I recommend sticking with an omega-6 to omega-3 ratio in your diet of 1:1 (or as close as you can get to that). Some studies even suggest even a ratio of 4-5:1, but I think that’s still too high.

As I explained in my article busting the top myths about red meat, nutritional science can often be misleading because most people don’t know the difference between clinical trials, systematic reviews (or meta analyses) and observational studies. The latter can only show correlation, not causation.

In other words, if you read that saturated fats are linked with (or associated with) cardiovascular risk factors or high blood pressure, that does not mean that saturated fats cause heart attacks (or high blood pressure).

The same is true for studies that link the consumption of unsaturated fats to lower serum cholesterol, LDL or better heart health; a link doesn’t indicate causation.

To learn more about this issue, check out this blog post from Chris Kresser on how to read and understand scientific research.

The term “essential” refers to the fact that the body can’t make them. In other words, we have to get these fatty acids from dietary sources. What that means is that all of the fatty acids discussed in this article have health benefits if consumed in the proper amounts.

That’s right, even the pro-inflammatory linoleic acid is an essential component of cell membranes. But that fact that a little bit of something is good doesn’t necessarily mean that more is always better. When it comes to linoleic acid, exceeding a dietary intake that’s consistent with human evolution can be detrimental to your health, as I explained in this article.

No, there is no reason to supplement with a product that contains omega-6 fatty acids, considering how much omega-6 you have in your diet already. Also, omega-9 fatty acids are not essential and there is no reason why you would need to get them via supplementation.

Also note that many omega-3 supplements are rancid and should be avoided. Instead, get your omega-3 from whole-food sources (e.g., fatty fish and beef suet) or pick high-quality supplements, such as the ones from Designs for Health.

Saturated vs. Polyunsaturated Fats: Final Thoughts

Thanks to misguided dietary advice from our governments and healthcare professionals, we’re consuming unprecedented amounts of polyunsaturated fatty acids, and especially linoleic acid.

That has led to a dramatic increase in rates of obesity, cardiovascular disease and other metabolic health issues over the past few decades.

Coupled with the consumption of highly-processed and hyper-palatable food-like substances, such as crackers, cookies and margarine, we’ve become a nation of sick people.

It’s time to change that and to return to a species-appropriate diet that consists predominantly of saturated and monounsaturated fats, meat, organs and some of the least-toxic plants. Industrial seed oils and highly-processed carbs have no place in such a diet.

The problem is that getting rid of all the oxidized PUFAs in your body can take years because they’re stored in fat tissue. So you better start removing these inflammatory fats and oils from your diet today and get your inflammatory markers back to where they should be.

But now I’d like to hear from you! After reading this, how do you feel about increasing your intake of saturated fat and dietary cholesterol? Does it still make you nervous considering what you’ve been told for decades?

If so, I don’t blame you. I can tell you that even among my family, there is still a lot of hesitation. Vegetable oils and veggies, in general, are considered healthy whereas meat and eggs are not. But the science is pretty clear and so is evolution. So give it a try and if you have any further questions or concerns, just shoot me an email!

Michael is a healthy living enthusiast and CrossFit athlete whose goal is to help people achieve optimal health by bridging the gap between ancestral living and the demands of modern society.

Medical Disclaimer

The information shared on this blog is for educational purposes only, is not a substitute for the advice of medical doctors or registered dieticians (which we are not) and should not be used to prevent, diagnose, or treat any condition. Consult with a physician before starting a fitness regimen, adding supplements to your diet, or making other changes that may affect your medications, treatment plan or overall health. MichaelKummer.com and its owner MK Media Group, LLC are not liable for how you use and implement the information shared here, which is based on the opinions of the authors formed after engaging in personal use and research. We recommend products, services, or programs and are sometimes compensated for doing so as affiliates. Please read our Terms and Conditions for further information, including our privacy policy.

Hi Michael,

This was a great article to read. One thing I’m wondering about is why lard and duck fat are often recommended on animal based / higher saturated fat diets, while the animal meat itself isn’t due to pig and duck being monogastric animals which don’t readily convert PUFAs to saturated fats. Could you shed some light on this?

Hi Marie!

Great question! Neither lard nor duck fat would be my first choice considering they’re higher in omega-6, unless, maybe, if the lard came from pigs that had no corn/soy in their diet and the lard came from wild ducks. But even then, I’d prefer tallow or fats from ruminant animals.

However, when compared to canola oil, I’d go with the fat of mono gastric animals :)

Hello, thank you for the great and informative thesis.

Nose-to-tail carnivore over here. Inspired by Paul’s Carnivore Code book, been on this diet (plus fruits and honey) for about 4 months now and have never felt better.

I just have a quick question:

We have been acquiring our beef from a trusted local rancher who offers grass-fed grass-finished beef. But it’s very costly. Given the current economic crisis we can’t always order a half-cow and must sometimes rely on meat from Costco. That being said, I wonder how much PUFA is present in the meat of those cattle which are fed a conventional hay/grain/oils- diet, and what would be your recommendation when we must buy more affordable meats outside of our trusted local ranchers (what types of cuts, etc)

Thank you in advance, and look forward to hearing back from you.

Sincerely,

A fellow carnivore

Hey Elias,

I wouldn’t worry too much about it. The amount of omega-6 is grain-fed meat is still relatively low compared to consuming certain plants or processed food made with seed oils. So I’d buy the best meat you can afford and don’t shy away from buying chewier cuts for the slow cooker. You can find reasonably priced roasts at Whole Foods. There is even grass-fed steaks at Aldi for much less than what you might pay locally.

Cheers,

Michael

very informative.

I appreciate all the perceptions you addressed, but wasn’t as aware of some of the Omega-3 risks and LDL perceptions/science as you have now enlightened me about. I moved off an Omega supplement a while ago and I’m so glad I have; I am balancing my diet naturally. Thanks for making more information available!

You’re most welcome, Rose!

Hi Michael –

Thank for posting this thorough review. I’d been searching for the 4% PUFA reference for a while, after reading about it in the Perfect Health Diet. After another rise in my LDL and ApoB recently, I’d been toying with a move to more MUFA in place of SFA, but even on a 30/40/30 macros breakdown found it difficult to limit SFA without crossing the 4% threshold on PUFA.

Since adopting a roughly 25/55/20 macros split, dominated by SFA in the form of eggs and grass-fed butter and ruminant meat, my overall health has improved. I’ve had a particle analysis done with overhelmingly Pattern A large fluffy particles. My CRP is low (0.5) and my triglycerides are low (0.9). My HDL is high at 1.8mmol. I also have very low inflammation. While I know this site is not medical advice, it was good to read about a very similar story and your confidence – shared by my doctor – that this would put me in good health and I have little to be worried about.

While monounsaturated fats seem like miracle foods, and I’m happy to eat olive oil, avocado and macadamias daily, they don’t seem to be have been consumed in modern quanitities for very long. I found your reference to the presence of both PUFA AND MUFA in arterial plaque fascinating – do you know if much more has been done on this in humans since that paper in 1995?

Thanks,

Alex

Hey Alex,

Thanks for the feedback, I appreciate it! I haven’t found any good studies on the subject other than the relatively old article I referenced. But as long as my blood markers and overall health are where they are, I’ll continue down that path :)

PS: Apologies for the late reply. Your comment got accidentally deleted by my anti-spam plugin and I just found out about it.

I found your article very concise and conscious of how you presented your information.

I found I could digest and absorb the information efficiently.

I’ve been recommended the paleoketo diet by a hospital in order to help manage my Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. I’m 60 years of age and am not overweight. I do yoga, meditation and am a pescatarian. My consultant was surprised at my cholesterol levels as both my LDL & HDL are high. I was perplexed as I don’t fall into the classic profile of a person who usually has bad cholesterol- I avoid fried food, no diabetes indicators in my family history I’ve also got low blood pressure. I avoid refined foods, sugar and processed foods in general. This article has given me hope and explained that my HDL level is not necessarily an issue. I’m going to adjust the kind of oil that I use as I’m fond of sesame oil.

Hi Nkechi,

You mean you realized that your high LDL is not necessarily an issue, right? High LDL is often not an issue with you follow a high-fat low-carb diet, such as a ketogenic diet.

However, be careful with sesame and all other seed oils as they’re usually high in inflammatory fatty acids, such as omega-6. My recommendation is to stick with animal fats (lard, tallow, duck fat, ghee…), avocado oil, olive oil, coconut oil.

All the best!

Michael

Thank you for this valuable information! I hope that at least one primary care doctor reads this and truly helps at least some of his or her patients to employ this powerful information for preventing so many health issues which are diet related(not just weight control).Keep up the good work! PS I had a stroke a few years ago after following the SAD(standard American diet) all my life. Now living in ketosis full time. 30 lbs lighter and great lipid reports as well as level energy levels all the time. BTW 65 years old.