If it isn’t already, one of the main reasons you exercise should be to retain or increase muscle mass. Far more than simply helping us look good, having adequate muscle is fundamental to not only our immediate cardiometabolic health but also to how long we live well.

Without any doubt, the most important factor in retaining and building muscle is what we do to the muscles themselves — the workout. However, what we put in our mouths after the workout can help.

The idea of a post-workout meal or supplement is rich with dogma, sprinkled with some data. Certainly, every weightlifter, professional or pedestrian, has their own ideas about what to eat to optimize muscle recovery and growth (and to minimize muscle soreness).

While there’s certainly room for tailoring a recovery meal based on needs and preferences, there are some common pillars that should be the foundation of all plans.

Aminos Matter

Let’s make the first pillar absolutely clear: nothing is more important to recovery than amino acids. These building blocks of dietary protein are the single most relevant stimulus in promoting the growth of new protein within a muscle cell.

Amino acids are so essential to muscle cells (and all other cells!) that they have their own distinct mechanisms of being transported into the cell — doorways that only amino acids can use.

Exercise opens those doors. In fact, just the act of working a muscle will stimulate the movement of amino acids into the muscle. But what if we can help that process?

That’s where optimizing a post-workout recovery meal comes in.

Not all amino acids count the same when it comes to building and maintaining muscle. Across the numerous amino acids are various classifications, some of which are based on the structure of the amino acid.

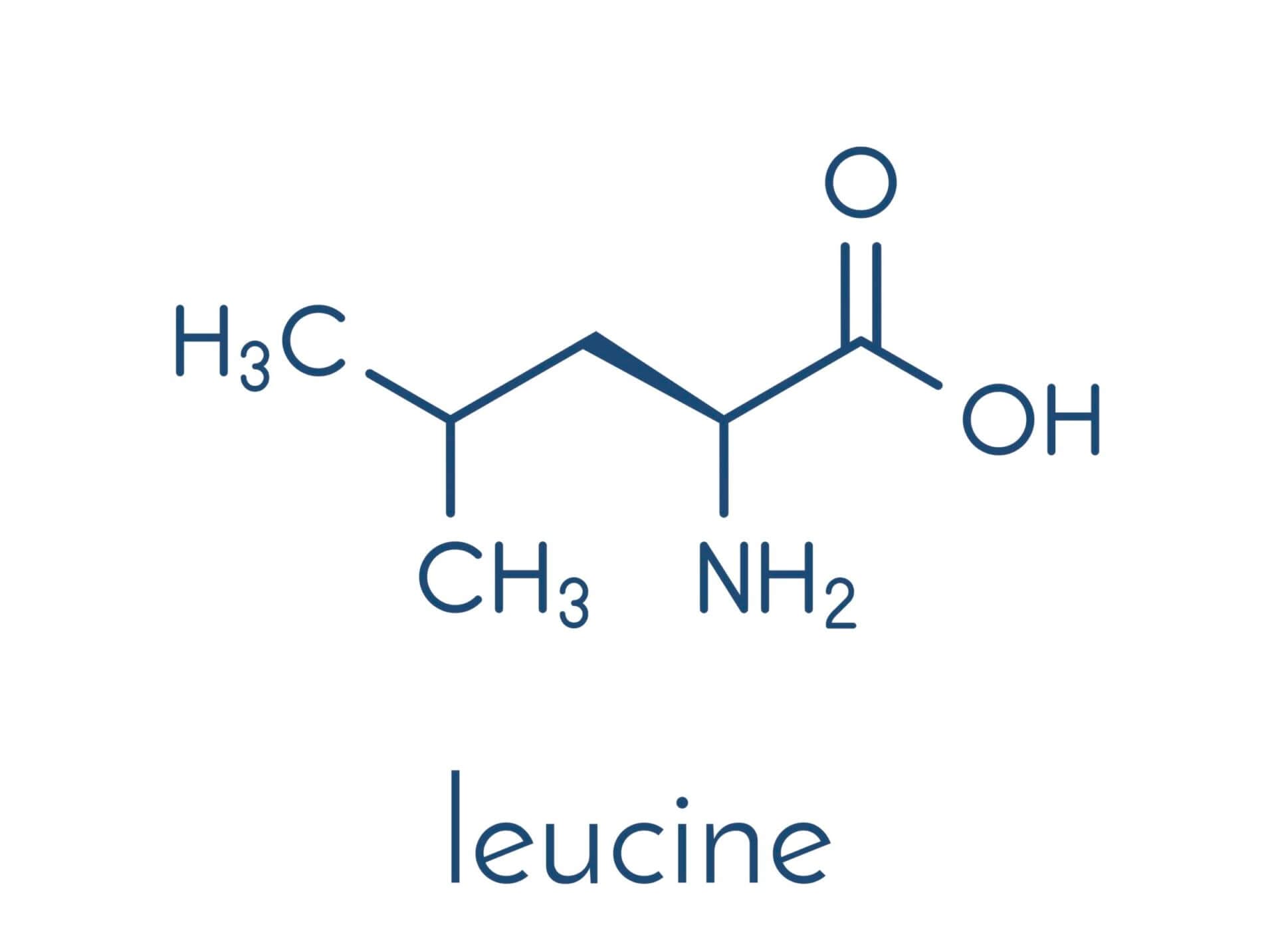

Within this classification are the three amino acids known as the branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs): valine, isoleucine and leucine.

Collectively, the BCAAs matter not only because they represent the single largest “block” of amino acids that make up muscle protein, but also because they are essential. In other words, our bodies cannot produce them — we have to eat them.

Long-touted for their collective benefit in muscle building, the truth is actually simpler: this trio is really best as a solo act.

Valine and isoleucine don’t matter nearly as much as leucine, which appears to play the most essential role and elicits the benefit on its own.

Even if a diet is generally deficient in protein, simply providing leucine is enough to overcome the deficiency and stimulate muscle protein growth.

Digestion/Absorption Matters

It’s one thing to ensure you’re consuming the proper and necessary amino acids in your diet, but it’s another to ensure they get from your intestines into your blood.

This process involves digesting the protein into smaller bits (polypeptides), then actually absorbing those linked amino acids into the bloodstream.

The main process of digesting a protein starts in the small intestine, where the protein interacts with enzymes that the pancreas produces. This digestive process is essential for the next step of absorption — if we can’t digest (i.e., break down) the larger protein molecules into their components, we can’t absorb them across the intestines and into the blood.

One of the most remarkable and overlooked aspects of protein digestion is that protein doesn’t digest as well alone as it does with its macronutrient mate, which is fat. When fat is consumed, it stimulates the release of bile salts into the intestines.

Classically, bile salts are only considered as a factor for digesting fats — they physically pull dietary fats apart, helping them get digested further.

However, these same bile acids actually enhance the actions of the protein digestive enzymes. This is very likely why some people complain about stomach discomfort when taking a protein supplement that is pure protein — they need the added fat, and the addition of bile acids, to help digest that protein.

This is most certainly reflected in nature, where the best proteins come with fat.

These best proteins, defined by not only having the right amino acids but also by the degree of intestinal absorption, always come with fat — dairy, meat, and eggs.

Lest you think combining protein with fat as nature intended is simply a matter of the intestines, the consequences of this macronutrient combination are very real, including at the level of the muscle cell.

A study that explored muscle growth in humans made this clear. As noted earlier, exercise alone can stimulate some degree of muscle growth. This study combined exercise with a post-workout protein load and found that muscle growth was larger than with exercise alone.

Interestingly, when the study group consumed a post-workout protein and fat load, muscle growth was the greatest among all the measured interventions.

One revelatory aspect of that study was the ratio of the macronutrients. The scientists used a 1:1 ratio of the two macronutrients, providing a mass of protein with an equal mass of fat. This is perfectly reflected in one of nature’s best protein sources: the humble egg.

Unfortunately, modern protein supplements completely miss this aspect of muscle science by only providing protein. It’s certainly a more affordable strategy; after all, including real fats in a protein supplement is not cheap.

But it means the consumer of the protein-only supplement is wasting money; they’re not getting all the protein they think they are, and the result is that they’re likely not getting the post-workout muscle recovery they think they are.

The value in combining fat and protein is made all the more relevant in the modern push for plant-based proteins. Plants are generally less-than-optimal sources of protein (indeed, objectively worse than animal-based sources). At least a part of this comes from the fact that plant proteins are essentially devoid of fat.

Another unsavory aspect of plant-based proteins that reduces absorption is the presence of antinutrients.

Yes, plant proteins actually are known to contain molecules that literally block the digestive enzymes from doing their jobs. These include molecules like trypsin inhibitors and tannins, which can block up to 50% of the digestion of proteins from sources like soy, wheat, pea, and more.

Carbohydrates Don’t Matter

You may have noticed a theme among the best proteins mentioned earlier (meat, dairy and pasture raised eggs): while they’re rich in protein and fat, they’re devoid of carbohydrates. Once again, it’s almost as if nature knows what it’s doing.

So often, people will deliberately seek to include carbohydrates with protein in their post-workout recovery meals or supplements, because they believe the insulin spike from the carbohydrates will facilitate muscle building.

Unfortunately, this simply doesn’t happen. Adding carbs to protein provides no muscle-building benefit beyond the protein alone.

Insulin Matters

However, this isn’t to say that insulin doesn’t matter to muscle protein. It does, but not in the way many people think.

Insulin is likely necessary for a baseline movement of amino acids into the muscle, but pushing insulin up doesn’t make this process work any better; its main job is to prevent the breakdown of muscle protein.

This is likely why adding carbs to your post-workout protein doesn’t move the needle with regard to recovery and muscle growth.

Speaking of insulin, there’s one more notable aspect worth mentioning: the muscle needs to be able to respond well to insulin in order to benefit from its muscle-protecting effect. This becomes a problem when a muscle cell becomes resistant to insulin’s effects.

Now, you might be thinking this doesn’t concern you.

But it might.

Insulin resistance is the most common health disorder and is often undiagnosed.

When a muscle becomes insulin resistant, two consequences follow:

Combined, these factors make muscle recovery and growth a challenge.

Fortunately, exercise is a great way to maintain or improve muscle insulin action. But tragically, consuming carbohydrates after a workout actually mitigates some of the insulin-sensitizing effect of the exercise itself.

That’s right: those post-workout carbs may be making things worse.

Frequently Asked Questions

The best thing you can do is to improve blood flow to the affected muscle groups by moving your body, sauna sessions, foam rolling, percussion therapy or even electric muscle stimulation.

Also, don’t forget about the importance of sleep for your recovery process. During certain stages of sleep (slow-wave and REM sleep), the body releases hormones, such as testosterone and human growth hormone, that play important factors in muscle recovery and growth.

So make sure you get a good night’s sleep before and after intense workouts or competitions.

Exercise is a stressor that often results in just enough damage to encourage the body to grow more and stronger muscle tissue. That’s called exercise-induced hormesis, and it’s a necessary process in building lean muscle.

Heat increases blood flow and cold inhibits blood flow. As a result, the only reason why you would want to use cold therapy (i.e., ice packs) is to stop the bleeding caused by an injury to muscle tissue (e.g., a severe tear or strain). In all other cases, heat is your friend because it increases blood flow and the transportation of nutrients into your muscle tissue.

No. While most people think there’s a narrow window of time where you need to eat protein (and fat!), it’s actually more like a barn door.

There’s a very large period of time after and even before a workout wherein you want to consume a leucine-rich protein source.

In fact, to a degree, fasting might even “prime the pump” for muscle growth by stimulating the release of growth hormone.

Resting doesn’t mean sitting on the couch all day or not moving your body at all. Anything that facilitates blood flow without stressing your body by inflicting further damage is beneficial for the recovery process.

As a result, I encourage light physical activity, using a foam roller and other techniques — even on rest days.

That depends on what type of fuel your body is used to. If you run predominantly on carbohydrates (glucose) as a source of fuel, consuming carbs can certainly help your body replenish empty glycogen stores.

However, if you’re fat-adapted and use fat (fatty acids or ketone bodies) as your primary source of fuel, there is no need to consume carbs to replenish your glycogen stores.

In fact, studies have shown that elite athletes who are on a ketogenic diet replenish their glycogen stores at the same rate as athletes who run on carbs.

The likely reason for that is the body’s ability to make glucose from non-carbohydrate sources via a process called gluconeogenesis.

Proper hydration is incredibly important for exercise performance and recovery to ensure that the body can transport nutrients to where they’re needed.

The same goes for electrolytes (sodium, calcium, magnesium and potassium). So make sure you get enough of these minerals through diet (especially salt) and consider using supplements during intense workouts, if necessary. I use Magnesium Breakthrough from biOptimizers.

Overtraining is a general (i.e., whole-body) condition wherein the body is unable to keep up with the demands placed on it. Basically, it’s when the exercise overwhelms recovery.

The most important aspect of avoiding overtraining is to adequately rest, of course. This can possibly be accelerated and enhanced by unconventional strategies, including sauna and breathing techniques to promote the parasympathetic nervous system.

Nevertheless, ensuring both adequate calories and the right type and amounts of proteins (i.e., animal proteins) and fats can help narrow the recovery window.

Take-Away Thoughts

Ultimately, the best way to ensure you’re facilitating muscle growth following a workout is to focus on protein and fat instead of grabbing a glass of chocolate milk.

By building recovery on a foundation of a balanced ratio of animal-sourced proteins and natural fats, you can rest (and recover) well knowing you’re not only maximizing protein digestion, but also providing the muscle with the best nutrition.

For the best recovery, macros matter!

Benjamin J. Bikman, Ph.D. is a metabolic research scientist and a speaker on human metabolism and nutrition. His book Why We Get Sick offers a thought-provoking solution to the modern plague of insulin resistance and offers tips for reversing pre-diabetes, improving brain function and shedding fat. He is the founder of HLTH Code, which makes healthy meal replacement shakes.

Medical Disclaimer

The information shared on this blog is for educational purposes only, is not a substitute for the advice of medical doctors or registered dieticians (which we are not) and should not be used to prevent, diagnose, or treat any condition. Consult with a physician before starting a fitness regimen, adding supplements to your diet, or making other changes that may affect your medications, treatment plan or overall health. MichaelKummer.com and its owner MK Media Group, LLC are not liable for how you use and implement the information shared here, which is based on the opinions of the authors formed after engaging in personal use and research. We recommend products, services, or programs and are sometimes compensated for doing so as affiliates. Please read our Terms and Conditions for further information, including our privacy policy.

I am attempting to merge a low insulin, 6-hr daily feeding window, with a monthy alternation between periods of muscle growth and a 5-day water fast. I’m 65, recovered diabetic and in good cardio shape and very well fat-adapted. I can put 65 mi on my bike on day 5 of fast. Can I manage enough muscular growth during anabolic periods to offset the fasting losses? I really feel the fasting and autophagy has been great for my recovery (I lost my liver to NASH).

Hey Jim,

everyone gains and loses muscle tissue at different rates, so it’s hard to tell how your body will react without trying it. 5-days is certainly stretching it and I wouldn’t be surprised if you lost some meaningful muscle tissue during that time. So I’d try it out and see how you feel (and look in the mirror). If necessary, shorten your fasts a bit (maybe to three days).

PS: Apologies for the late reply. Your comment got accidentally deleted by my anti-spam plugin and I just found out about it.

I really enjoyed this article, however, how much fat do you need to incorporate with the protein? Is an ounce of macadamia nuts enough? A tablespoons of peanut butter? Olive oil with a salad? Any suggestions?

I usually shoot for a 1:1 ratio of protein and fat. So if your shake has 20 grams of protein, add 20 grams of fat.

As far as the fat source is concerned, I typically use MCT oil (liquid or powder) when mixing it into a shake.

If I eat a regular meal, I just go with tallow, ghee, coconut oil or butter.